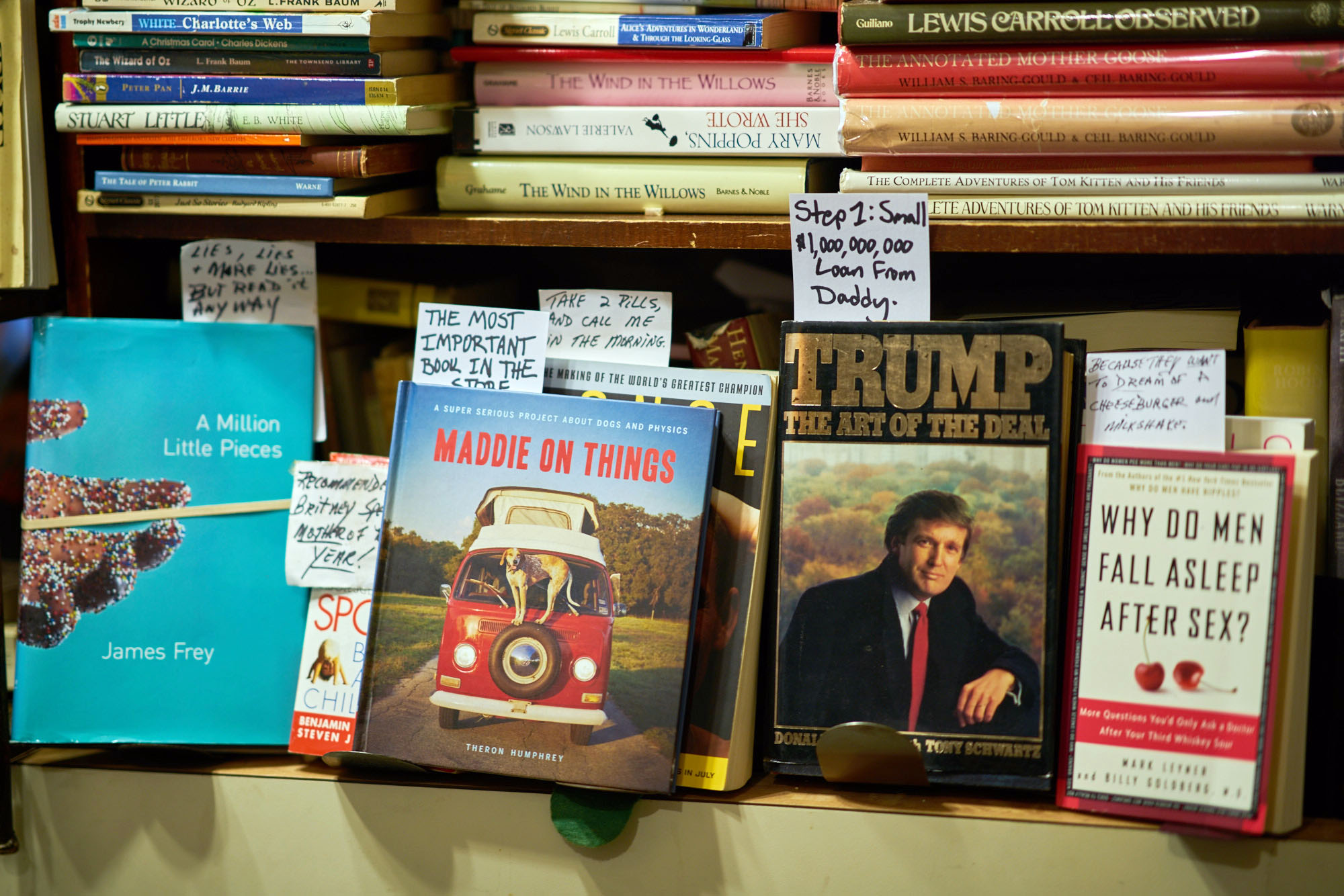

Worth a stop for the curation and editorial license.

by Sisi Wei, Olga Pierce and Marshall Allen:

Guided by experts, ProPublica calculated death and complication rates for surgeons performing one of eight elective procedures in Medicare, carefully adjusting for differences in patient health, age and hospital quality. Use this database to know more about a surgeon before your operation.

The relationship of many western consumers to the internet giants is much like that which Václav Havel described for citizens living under the Soviet empire

The business model of the internet,” writes the security expert Bruce Schneier in his excellent new book Data and Goliath, “is surveillance.” States engage in it for their own inscrutable purposes and – as we know from Edward Snowden – they do it on a colossal scale. But the giant internet companies do it too, on an equally large scale. The only difference is that they claim that they do it with our consent, whereas the state doesn’t really bother with that.

A big mystery for those of us who worry about the long-term implications of surveillance is why internet users seem generally to be unconcerned about this. It varies from culture to culture, of course: the citizens of Germany are more perturbed about it than are the British; but that’s understandable because large numbers of Germans had the experience of living under the analogue surveillance run by the Stasi. And in the US, endemic suspicion of the federal government keeps some people awake at night. But on the whole, across the world, internet users seem relatively unfazed by what’s going on.

Walt saw beyond what people were used to. They were used to the short cartoon.

It’s interesting how people cannot see beyond what they’re used to.

There’s a famous statement by Henry Ford that before the Model T if you asked people what they wanted, they would say, “A faster horse.”

My own partner at Pixar for 25 years, Steve Jobs, never liked market research. Never did market research for anything.

Chris Dillow writes,

If extensive knowledge is possible, then bosses might be able to manage big companies well. If not, then centrally planned companies will be inefficient. Sure, perhaps competition will eventually weed out egregious incompetence, but market forces might not grind so finely as to eliminate all inefficiency

Pointer from Mark Thoma.

I cannot emphasize enough how much I agree with this. Because I spent 15 years in business, I got an opportunity to see large organizations close up. I saw that in a large business, the top management cannot keep track of more than about three major initiatives at a time. I saw that compensation systems have to be frequently overhauled, because employees learn to game any system that stays in place for more than a couple of years. I saw the “suits vs. geeks” divide, as specialists in information technology or financial modeling had difficulty communicating with executives who had only general knowledge.

The notion of large, efficient organization is an oxymoron. If you think that large corporations have overwhelming advantages, then you have explained why IBM still dominates the computer industry, while Microsoft and Apple never really got amounted to much of anything. I like to say that if you are afraid of large corporations then you have never worked for one.

I’ve been writing about exponential decline in the price of energy storage since I was researching The Infinite Resource. Recently, though, I delivered a talk to the executives of a large energy company, the preparation of which forced me to crystallize my thinking on recent developments in the energy storage market.

Energy storage is hitting an inflection point sooner than I expected, going from being a novelty, to being suddenly economically extremely sensible. That, in turn, is kicking off a virtuous cycle of new markets opening, new scale, further declining costs, and addition

By Alex Tabarrok and Tyler Cowen:

Might the age of asymmetric information – for better or worse – be over? Market institutions are rapidly evolving to a situation where very often the buyer and the seller have roughly equal knowledge. Technological developments are giving everyone who wants it access to the very best information when it comes to product quality, worker performance, matches to friends and partners, and the nature of financial transactions, among many other areas.

These developments will have implications for how markets work, how much consumers benefit, and also economic policy and the law. As we will see, there may be some problematic sides to these new arrangements, specifically when it comes to privacy. Still, a large amount of economic regulation seems directed at a set of problems which, in large part, no longer exist.

Countries in the front line of Moscow’s “weaponisation of information”, in the words of Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss, two analysts, have long sought to draw attention to the problem. The European Union is at last listening. Heads of government, meeting in Brussels as we went to press, were expected to ask Federica Mogherini, the EU’s foreign-policy chief, to produce a plan to counter Russia’s “disinformation campaigns” by June. Before that the EU will launch a task force (working name: Mythbusters) charged with monitoring Russian media, identifying patent falsehoods and issuing corrections.