Wikipedia on Molokai.

When the Last Patient Dies by Alia Wong

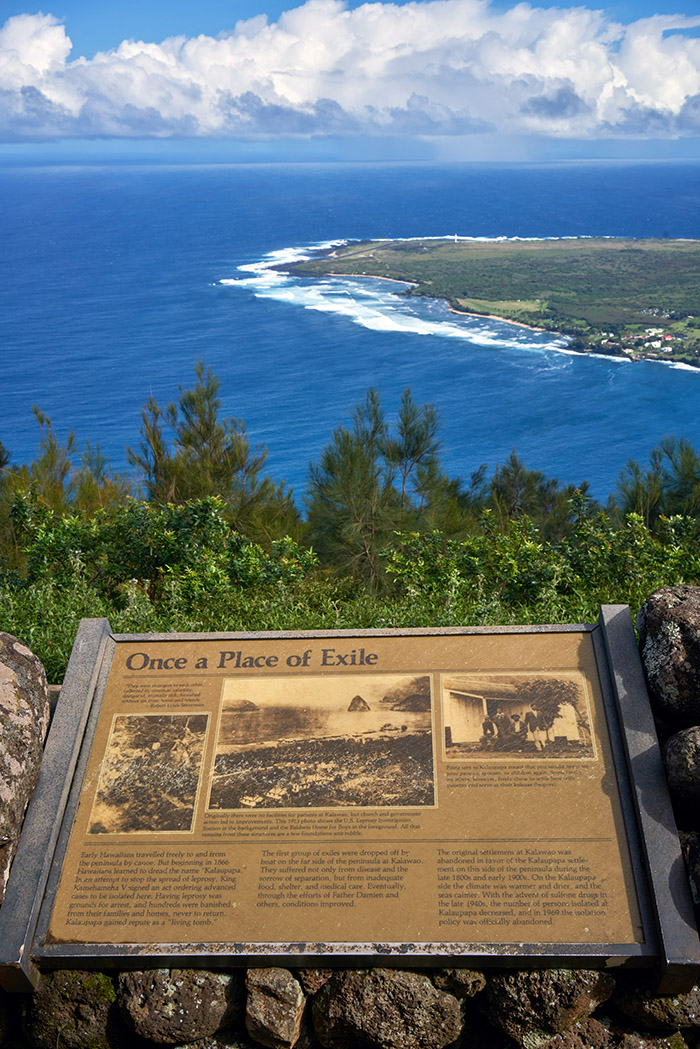

Not so long ago, people in Hawaii who were diagnosed with leprosy were exiled to an isolated peninsula attached to one of the tiniest and least-populated islands. Details on the history of the colony—known as Kalaupapa—for leprosy patients are murky: Fewer than 1,000 of the tombstones that span across the village’s various cemeteries are marked, many of them having succumbed to weather damage or invasive vegetation. A few have been nearly devoured by trees. But records suggest that at least 8,000 individuals were forcibly removed from their families and relocated to Kalaupapa over a century starting in the 1860s. Almost all of them were Native Hawaiian.

Sixteen of those patients, ages 73 to 92, are still alive. They include six who remain in Kalaupapa voluntarily as full-time residents, even though the quarantine was lifted in 1969—a decade after Hawaii became a state and more than two decades after drugs were developed to treat leprosy, today known as Hansen’s disease. The experience of being exiled was traumatic, as was the heartbreak of abandonment, for both the patients themselves and their family members. Kalaupapa is secluded by towering, treacherous sea cliffs from the rest of Molokai—an island with zero traffic lights that takes pride in its rural seclusion—and accessing it to this day remains difficult. Tourists typically arrive via mule. So why didn’t every remaining patient embrace the new freedom? Why didn’t everyone reconnect with loved ones and revel in the conveniences of civilization? Many of Kalaupapa’s patients forged paradoxical bonds with their isolated world. Many couldn’t bear to leave it. It was “the counterintuitive twinning of loneliness and community,” wrote The New York Times in 2008. “All that dying and all of that living.”