Livable cities draw creative people, and creative people spawn jobs. Some places you’d never expect—small cities not dominated by a university—are learning how to lure knowledge workers, entrepreneurs, and other imaginative types at levels that track or even exceed the US average (30 percent of workers). Here are some surprising destinations from the data of the Martin Prosperity Institute, directed by Richard Florida, author of The Rise of the Creative class.

Case Study: Omaha, Nebraska

It’s only the 42nd-largest city in the US, but over the past two decades, Omaha has been transformed into one of the Midwest’s most vibrant cultural hubs. Here’s how the rebirth happened, starting in the ’90s.

Indians work miracles on a shoestring

Tileshwar Prasad concentrates fiercely on every step, one foot in front of the other, staring at the wall ahead as he learns how to walk again.

At the end of his careful parade, he is asked how he feels with his new limb, a prosthetic foot built from rubber and wood, and a new knee made of nylon and a handful of bolts.

For the first time in a decade he is able to stand unaided, hands on hips and back straight.

Life on the open road

My Cool Campervan. By Jane Field-Lewis and Chris Haddon with photography by Tina Hiller. Pavilion; 160 pages; £14.99.

THE classic VW camper van is a venerable vehicle on which rides–usually rather slowly–a carefree image of life on the open road. They can often be found in the narrow British lanes leading to the surfing beaches in Cornwall in the summertime. But as old ones in good nick can cost £20,000 ($33,000) or more, many of their owners are more likely to be trying to recapture their lost youth than hanging ten.

There are many variations of the VW camper van, not least because until 2005 Volkswagen never made a camper itself, but produced vans for transporting people and goods which others converted with the addition of caravan-style living accommodation. And it was not just VWs which received such attention, as “My Cool Campervan” shows in a collection of photo essays.

Doonesbury’s take on the troubles of vets: A response from Garry Trudeau

As I’m old enough to recall the stereotypes that formed around Vietnam veterans, I’m well aware of this danger. The purpose of my stories has been to participate in the national conversation about the costs of war. JPWREL and VICTOR are correct that the majority of warriors return home without invisible wounds, but it is by no means an “overwhelming” majority. There are an estimated 600,000 veterans (out of 2.2 million who’ve served in OEF and OIF) who are suffering from either stress disorders, MST, or the effects of TBI. The proportion is considerably higher than in previous wars because of multiple deployments and the aggregate number of consecutive days that participants are in a high-conflict environment, thus in a rolling state of stress and hyper-vigilance.

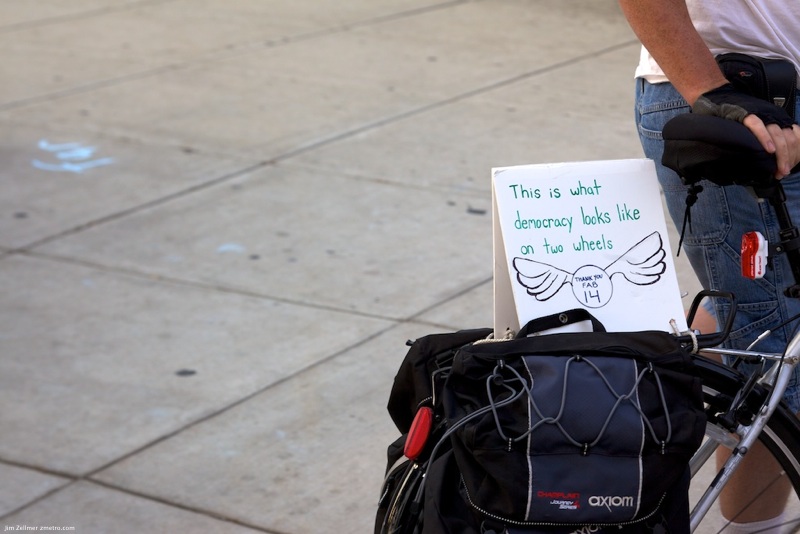

Monday Evening Scene

Visualizing Historical Data, And The Rise Of “Digital Humanities”

All historians encounter them, at some point in their careers: Vast troves of data that are undeniably useful to history–but too complex to make narratively interesting. For Stanford’s Richard White, an American historian, these were railroad freight tables. The reams of paper held a story about America, he knew. It just seemed impossible to tell it.

Impossible to tell in a traditional way, that is. White is the director of the Stanford University Spatial History Project, an interdisciplinary lab at the university that produces “creative visual analysis to further research in the field of history.” (The images in this post are taken from the project’s many visualizations.) Recent announcements on the project site announce “source data now available” (openness is one of the project’s tenets) on such topics as “Mapping Rio,” “Land Speculation in Fresno County: 1860-1891,” and “When the Loss of a Finger is Considered a ‘Minor’ Injury.”

Invasion of the body hackers

Michael Galpert rolls over in bed in his New York apartment, the alarm clock still chiming. The 28-year-old internet entrepreneur slips off the headband that’s been recording his brainwaves all night and studies the bar graph of his deep sleep, light sleep and REM. He strides to the bathroom and steps on his digital scale, the one that shoots his weight and body mass to an online data file. Before he eats his scrambled egg whites with spinach, he takes a picture of his plate with his mobile phone, which then logs the calories. He sets his mileage tracker before he hops on his bike and rides to the office, where a different set of data spreadsheets awaits.

“Running a start-up, I’m always looking at numbers, always tracking how business is going,” he says. Page views, clicks and downloads, he tallies it all. “That’s under-the-hood information that you can only garner from analysing different data points. So I started doing that with myself.”

His weight, exercise habits, caloric intake, sleep patterns – they’re all quantified and graphed like a quarterly revenue statement. And just as a business trims costs when profits dip, Galpert makes decisions about his day based on his personal analytics: too many calories coming from carbs? Say no to rice and bread at lunchtime. Not enough REM sleep? Reschedule that important business meeting for tomorrow.

The founder of his own online company, Galpert is one of a growing number of “self-quantifiers”. Moving in the technology circles of New York and Silicon Valley, engineers and entrepreneurs have begun applying a tenet of the computer business to their personal health: “One cannot change or control that which one cannot measure.”

America’s Hottest Investment: Farmland

This is usually a slow time of the year for farm sales. It’s past prime planting season. Yet, Sam Kain, Des Moines area manager for land sales at Farmers National, is busy. He has 3 auctions this week. Most of the 30 or so bidders who show up will be farmers. But an increasing number of people buying land these days have no intention of planting seeds, at least not themselves. They are investors and a growing number of them are getting interested in farmland.

Just how hot is American farmland? By some accounts the value of farmland is up 20% this year alone. That’s better than stocks or gold. During the past two decades, owning farmland would have produced an annual return of nearly 11%, according to Hancock Agricultural Investment Group. And that covers a time period when tech stocks boomed and crashed, and housing boomed and crashed. So at a time when investors are still looking for safety, farmland is becoming the “it” investment.

Orchid

Madison Farmer’s Market Scenes June 3, 2011