Here’s the image for the seven days to 1 November 2013, showing what version of Android was used by devices connecting to Google Play. Among them is “Froyo” (2.2) and “Honeycomb” (3.0). You can’t actually buy new Android devices running either of those. Yet both make up a notable proportion. The newest software, “Jelly Bean” (which actually covers three different numbering versions), accounts for 52.1% of the devices. Yet Jelly Bean is the software powering all those new Android phones – the ones that were the 80% in the past quarter. Clearly, the installed base doesn’t reflect the market share number.

Fine. But look, I saw some figures which said that last year Apple’s market share in tablets was 50%, and now it’s 30%. So Apple’s selling fewer tablets, right?

No, that’s not what that data tells you. What if the total number of tablets being sold has doubled? If last year there were 100m tablets sold in total, and this year 200m, then last year the figures would be 50m tablets and this year 60m. (Those aren’t the numbers. They’re just for illustration.)

So if you don’t have the absolute numbers, you don’t know what’s happening. Those sort of year-to-year comparisons can be helpful to visualise changes in the market landscape, but in fast-changing markets it’s not enough just to quote a single number. In some ways it obscures more than it reveals.

(Note that Google’s diagram above doesn’t have any numbers beyond the “share”; we don’t know if more devices connected to Google Play, and if they did, how many more that was compared to a month or year ago.)

Here’s an example, from YouGov in 2013, which showed Apple losing market share. Its share of the installed base had fallen, YouGov said, from 73% to 63% (note that unusually, this was an “installed base share”, not a “sales market share”).

And yet putting in the figures for how many units were bought showed that Apple had increased its installed base and increased its lead in that installed base. That’s counterintuitive. Yet it emerges directly from the calculation: the iPad installed base had gone from 2m to 5.3m; it had gone from having 0.6m more tablets than all its rivals combined, to having 3.1m more.

This doesn’t mean there won’t be more non-iPad tablets than iPads at some point. But it does mean that you need to enquire more carefully about absolute numbers when you’re presented with the word “share”. It’s absolute numbers that tend to matter.

Why Doctors Stay Mum About Mistakes Their Colleagues Make

Patients don’t always know when their doctor has made a medical error. But other doctors do.

A few years ago I called a Las Vegas surgeon because I had hospital data showing which of his peers had high rates of surgical injuries – things like removing a healthy kidney, accidentally puncturing a young girl’s aorta during an appendectomy and mistakenly removing part of a woman’s pancreas.

I wanted to see if he could help me investigate what happened. But the surgeon surprised me.

Before I could get a question out, he started rattling off the names of surgeons he considered the worst in town. He and his partners often had to correct their mistakes — “cleanup” surgeries, he said. He didn’t need a database to tell him which surgeons made the most mistakes.

Why I won’t get a Google+ Custom URL

Wait, wait, wait! Did they say that they may decide to charge me in the future? And that they may reclaim the URL or remove it “for any reason, without notice”?

A URL is an identifier. I’ll use it to identify myself on this service. I’ll link to it from my website. I may print it on a business card. Like Google said in their email, I’ll use it to “point folks to my profile”. But they can take it away for any reason or decide to charge me a (yet unknown) amount of money in the future?

Is Tesla Stock Running Out of Juice? “It’s Going to Be a Really Giant Facility”

The growth reported last week by Tesla Motors was impressive for a car company, let alone an American car maker still in its first year of volume production.

Tesla (ticker: TSLA) delivered 5,500 units of its sleek, all-electric Model S in the September quarter, producing revenues of $431 million—more than eight laps ahead of the $50 million achieved a year ago. The Palo Alto, Calif.-based company reported profits of $16 million, or 12 cents a share (if you set aside 40 cents worth of non-cash charges and lease accounting required by generally-accepted accounting principles).

Still, some investors had more extravagant expectations for the electric car maker run by celebrated entrepreneur Elon Musk. Most analysts had predicted deliveries for the quarter ending in September of near 6,000 cars; some, over 7,000. Then a Model S caught fire Wednesday after its battery got punctured by road debris. The driver escaped unharmed, but it was the second such incident in six weeks. From Tuesday to Friday, the car maker’s shares skidded 23% to $137.95.

…..

Musk also expressed confidence that Tesla could improve the cost efficiency of its power cells in the couple of years’ time required for the third-generation car to go into production. Meanwhile, Tesla is talking to potential partners about building a battery factory in North America.

“It is going to be a really giant facility,” Musk said. “We are talking about something that’s comparable to all the lithium-ion production in the world, in one factory. That’s big.”

Connected Cars & Advertising

We saw dashboards that had multiple presets allowing listeners to go from Pandora to NPR to and iTunes account in the same way they use radio presets now. We heard one young woman say, “Poor FM. I don’t listen to it anymore because I don’t have to,” as she described how she used to listen in her old car and how her new car has her spending time with other alternatives. Others on the video explained how they use radio, and it was clear that the hands-free environment changes how they access radio. And the radio people in the audience saw clear evidence for how they need to talk to their audience to make sure their station ends up as one of the alternatives sought out in the connected car.

Rosin pointed out that these connected car drivers will listen to radio only when radio offers unique, compelling, live and local content they can’t get anywhere else. One major advertiser, Fred Sattler, EVP/Managing Director for Initiative + in Los Angeles — he controls advertising for Hyundai and Kia — reinforced that radio won’t hang on to advertisers unless it is offering live, local content. He said syndicated air personalities are not unique enough to the local town, the local dialogue, and the needs of the local community to interest him as an advertiser in a connected car environment. That means some radio companies today are moving away from radio’s best remaining strength: unique local content.

It’s impossible to summarize a two-day event here, but a good starter is checking the Twitter hashtag #DASHAudio. Frankly, those not in the room who sent representatives to report back will get bullet points, but may well miss the essence of what those who were there received. I suspect every radio person who attended is already changing things about their strategy as a result of lessons learned at DASH.

And some of those lessons were hard to swallow. For instance, a panel of local car dealers who were previously giant radio spenders revealed why, in a couple of cases, radio has fallen off their radar and budgets have been shifted elsewhere. Jaws in the room dropped when we learned that part of the migration away from radio could have been prevented. More jaws dropped when dealers discussed radio’s lack of data and proof of performance compared to Pandora.

Peak Driving: What happened to traffic?

Remember traffic. It was only 30 years ago that people were complaining about getting stuck in traffic. But traffic peaked in the early part of the Century, and has fallen ever since. A few observers picked this up early, but many transportation agencies were in denial.

At the time, most analysts saw only two possible futures:

Future 1: Per capita vehicle travel resumes an upward path. This forecast was the proverbial ostrich with its sand-encased head.

Future 2: Per capita vehicle travel remains flat but traffic grows with population. Future 2 was already causing concerns as it created pressures on revenues (which were then dependent on falling gas tax revenue), yet DOTs still claimed needs for new construction and expansion of existing roadways despite overall falling demand. Some argued that though demand was falling on average, it wasn’t mean it is falling everywhere. And there were still unsolved problems that don’t go away just because travel isn’t increasing.

No one in power foresaw what actually happened.

Future 3: Per capita vehicle travel falls significantly.

At first people attributed this to the Great Recession of the late Bush Presidency, but the evidence was that travel began dropping before the economy tanked. Technology restructured personal travel the way it completely devastated many other industries (remember newspapers, the post office, buying records and paper books, your land-line phone, canals, long distance passenger trains, broadcast television, electric utilities, going to College). Just look at this picture of demand for mail:

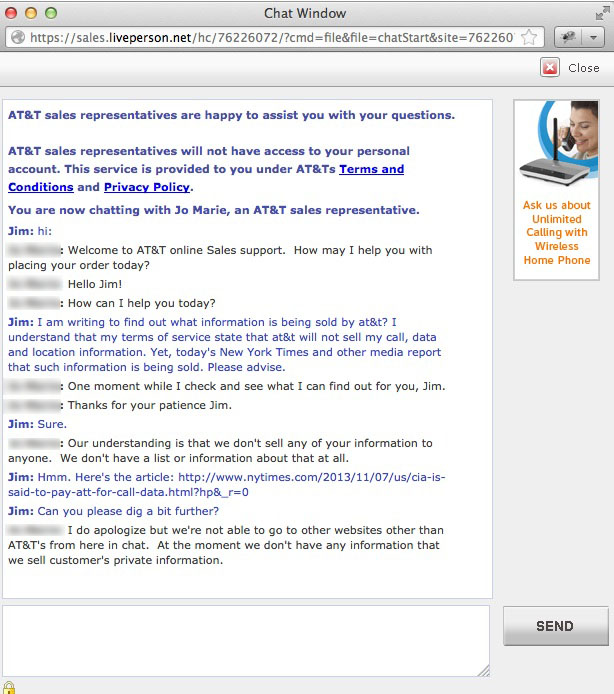

A Brief Chat with AT&T on Selling My Data

In light of Charlie Savage’s article on AT&T monetizing their user data, I asked “ma bell” about their data practices. A transcript follows:

Concert as an App: Fink & The Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra App. Delightful

The App Store.

Startup Idea: Used Car Leasing

Applications that open up spare capacity are a big deal. First eBay did it with the spare capacity of stuff in your attic. When counting pro sellers, eBay is the largest employer in the world. Next Airbnb took the spare capacity of your spare bedroom and turned it into the largest hotel in the world.

Cars could be next. There are ride sharing services, but they are modeled after Zipcars. That pattern works well for cities where driving is rare. For me, driving is extremely regular: get the kids to school, go to work, get groceries, etc. Getting a Zipcar daily doesn’t make sense, so the car sharing equivalents don’t either.

The model that does make sense is leasing, but leasing today stinks. First you have dealerships. Whether buying a new car, buying a used car, selling a used car, or leasing a new car, negotiating stinks, and it takes an actuary to figure out an optimal outcome. Selling a car on Craigslist is really cumbersome too, and Craigslist does nothing to smooth the transaction.

What If We Never Run Out of Oil?

As the great research ship Chikyu left Shimizu in January to mine the explosive ice beneath the Philippine Sea, chances are good that not one of the scientists aboard realized they might be closing the door on Winston Churchill’s world. Their lack of knowledge is unsurprising; beyond the ranks of petroleum-industry historians, Churchill’s outsize role in the history of energy is insufficiently appreciated.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911. With characteristic vigor and verve, he set about modernizing the Royal Navy, jewel of the empire. The revamped fleet, he proclaimed, should be fueled with oil, rather than coal—a decision that continues to reverberate in the present. Burning a pound of fuel oil produces about twice as much energy as burning a pound of coal. Because of this greater energy density, oil could push ships faster and farther than coal could.

Churchill’s proposal led to emphatic dispute. The United Kingdom had lots of coal but next to no oil. At the time, the United States produced almost two-thirds of the world’s petroleum; Russia produced another fifth. Both were allies of Great Britain. Nonetheless, Whitehall was uneasy about the prospect of the Navy’s falling under the thumb of foreign entities, even if friendly. The solution, Churchill told Parliament in 1913, was for Britons to become “the owners, or at any rate, the controllers at the source of at least a proportion of the supply of natural oil which we require.” Spurred by the Admiralty, the U.K. soon bought 51 percent of what is now British Petroleum, which had rights to oil “at the source”: Iran (then known as Persia). The concessions’ terms were so unpopular in Iran that they helped spark a revolution. London worked to suppress it. Then, to prevent further disruptions, Britain enmeshed itself ever more deeply in the Middle East, working to install new shahs in Iran and carve Iraq out of the collapsing Ottoman Empire.