When we hear the word ‘glamour’, we envision beautiful movie stars in designer gowns or sleek sports cars and the dashing men who drive them. For a moment, we project ourselves into the world they represent, a place in which we, too, are beautiful, admired, graceful, accomplished, powerful, wealthy, or at ease. Glamour lifts us out of everyday experience and makes our desires seem attainable. It creates a distinctive sensation of projection and longing.

What we find glamorous, like what we find funny, varies with personality and culture. But all glamour promises transformation and escape. In the image of a rising jet or a speeding convertible, a runway model or a martial arts hero, we experience the same dream: that we might soar beyond present constraints to become better, more accomplished, admired, respected and desired versions of ourselves. Glamour lets us project ourselves into new identities, imagining the ideal in the half-known.

As a result, glamour can be as powerful as it is pleasurable. By focusing previously inchoate yearnings, it motivates not just momentary fantasies but real-world action, from buying holidays and high heels to moving to new cities and pursuing new careers.

In fact, more than we like to admit, glamour influences our answers to the question “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

For young children, to whom the very idea of adulthood is alluring and exotic, the responses are almost always pure glamour: movie star, athlete, fireman, model, pilot, dancer, and, especially for the preschool set, princess or superhero. Children, their answers tell us, long for lives of power, excitement, beauty, fame, and significance.

So do adults. Whether experienced as children or young adults, the idealised professions we glimpse through books, movies, and TV shows often determine grown-up career choices – most of which have nothing to do with the stereotypically ‘glamorous’ trades of fashion or show business.

Your Outlet Knows: How Smart Meters Can Reveal Behavior at Home, What We Watch on TV

The research, which was published in 2012, measured how much power it takes to display certain programs on a television screen. Looking at seven movies and two television shows on five different brands of TV sets, the researchers found that each program had a unique power signature based on how much electric current was needed to show the images on the screen. Among the programs used for the tests was “Star Trek.”

Once the programs’ signatures were identified, the researchers found they could then match that information with data coming out of a smart meter. That meant a power company or other entity could mine this data to determine what a household was watching. The test was comprehensive enough to show the technique is broadly applicable and that there is an urgent need for stronger protections for smart-meter data, the researchers said.

As smart meters roll out around the world, the new technology has been met with anxiety and, at times, protests over security and privacy concerns. Last month, a protester was injured during an altercation with a water-utility employee at a demonstration in Ireland, and citizens’ groups in Australia, the U.S. and Canada have mounted campaigns against the installation of smart meters.

The coming digital anarchy

Bitcoin is giving banks a run for their money. Now the same technology threatens to eradicate social networks, stock markets, even national governments. Are we heading towards an anarchic future where centralised power of any kind will dissolve?

The rise and rise of Bitcoin has grabbed the world’s attention, yet its devastating potential still isn’t widely understood. Yes, we all know it’s a digital currency. But the developers who worked on Bitcoin believe that it represents a technological breakthrough that could sweep into obsolescence everything from social networks to stock markets… and even governments.

In short, Bitcoin could be the gateway to a coming digital anarchy – “a catalyst for change that creates a new and different world,” to quote Jeff Garzik, one of Bitcoin’s most prolific developers.

It’s already beginning. We used to need banks to keep track of who owned what. Not any more. Bitcoin and its rivals have proved that banks can be replaced with software and clever mathematics.

Former Genesis drummer Chris Stewart publishes his latest dispatch from Andalusia

Stewart is one of nature’s enthusiasts. He’s also one of her more impulsive handymen. He’s also a farmer. The combination of all these has made him a best-selling writer. It’s a quarter-century since he spent virtually everything he possessed (about £25,000) to buy a small, primitive farm, on the wrong side of the river, in the mountainous Alpujarra region of Andalucia in southern Spain. He and his wife Ana had driven around the region and idly wondered if they might ever consider living there; but when he thrust the cash into the hands of Pedro Romero within minutes of seeing El Valero, he was going on the purest impulse.

Telling his wife what he’d done wasn’t easy. And, almost immediately, awkward questions crowded in: how could he fix a domestic water supply? What to do about locals’ plans to flood the valley and build a dam? And what about Pedro, who showed no immediate, or long-term, intention of moving out?

Solving these problems, and transforming this patch of Nowheresville into a sun-drenched idyll took years of back-breaking toil and learning-on-the-job DIY, of helpful neighbours and impossible bureaucrats. It also begat Driving Over Lemons, published in 1999 to loud acclaim and huge sales. Successive books, drawing from the same rich well of rustic anecdote and expatriate self-consciousness, followed in 2002 (A Parrot in the Pepper Tree) and 2006 (The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society), and Last Days of the Bus Club is out this week.

Accidental Explorer

Author William Dalrymple has been in love with India for 30 years and written many books about the country. He tells Selma Day that it was just pure chance that he ended up there

Last month saw the famed Jaipur Literature Festival arrive at the Southbank Centre, showcasing South Asia’s literary heritage through a day of talks, music and readings. We caught up with festival director William Dalrymple, the author of nine books about India and the Islamic world, including White Mughals, The Last Mughal and his most recent, Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan.

When did your fascination with India begin?

Knowing nothing about India and with very little interest, I ended up there by total accident, aged 18. I was in a state of total confusion for about a week and then fell rather hopelessly in love with it and it’s a relationship that has continued until this day. It’s 30 years this year.

Business jargon: Squaring the circle

“Putting together the pipelines,” was how Pfizer chief executive Ian Read explained his proposed takeover of British drugmaking rival AstraZeneca.

“Let’s make sure we get good capital allocation… build a culture of ownership… flexible use of financial assets… productive science… opportunity to domicile… putting together the headcount,” were among his phrases as he faced MPs last month, much to the frustration of committee members.

“I asked a simple question,” committee chairman Adrian Bailey said at one point.

Use of jargon is not a new phenomenon, but businesses are leaving their customers and even their own staff scratching their heads about where their firms are going and where they themselves stand.

“This jargon is tribal and reinforces belonging,” says Alan Stevens, director of Vector Consultants, which advises companies on culture. “It’s part of the psyche. But it’s not useful.”

TV Rights Spaghetti: Sports App User Experience and the French Open

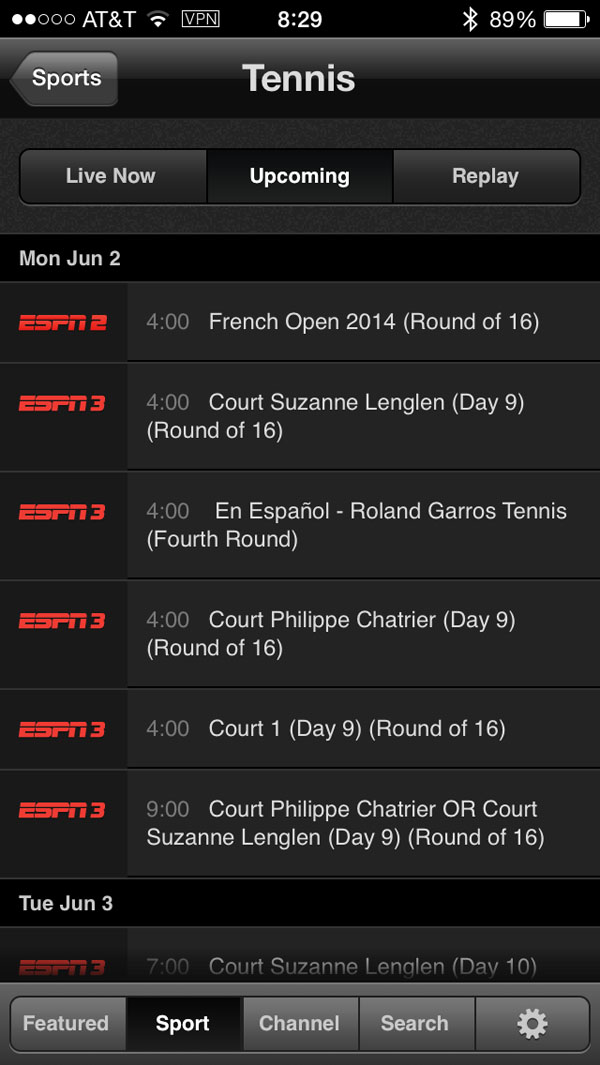

A tennis Dad and occasional recreational player, I enjoy watching a few pro tour matches. The French Open beckoned Saturday morning so I tapped the “WatchESPN” iOS app, tapped “Tennis” and….. saw no live events until Monday!

Strange.

I knew the French Open was underway, + 7 hours from my Madison home.

So began a quick survey of sports television rights spaghetti, one that included four apps!

I set my “virtual location” to Espoo, Finland using F-Secure’s “Freedome” VPN app. I then installed the French Open app seeking a live court by court video stream. Alas, I was unsuccessful. Perhaps the secret is buried deep in the app, but I failed to find it.

I searched online a bit to see if there were other apps streaming the event, but, after a few minutes gave up and moved on.

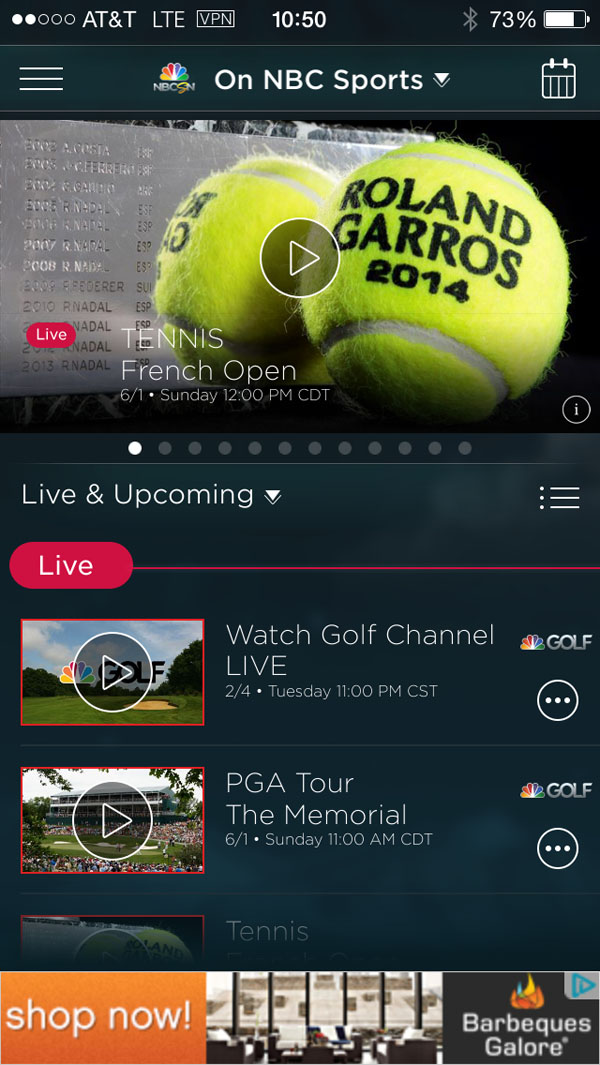

A “major” tv network must have acquired certain rights to the French Open, and indeed, in the States, NBC (parent, GE) is it.

I installed the NBC Sports app and found that a live stream + commercials was available from 11:00a.m. CDT to 2:00p.m. CDT. (The Murray – Kohlschreiber match went late and continued the next day). NBC’s sportscasters cut to hockey several times and later apologized that they would stay with tennis and go to a College Rugby contest when the Murray – Kohlschreiber match was complete that evening (afternoon).

The NBC Sports App mirrored broadcast TV’s schedule….. Astonishingly, the tennis fan who wished to see other matches, mostly earlier in the day, could not view any events beyond those available on broadcast tv. In fact, they did not exist within NBC’s app.

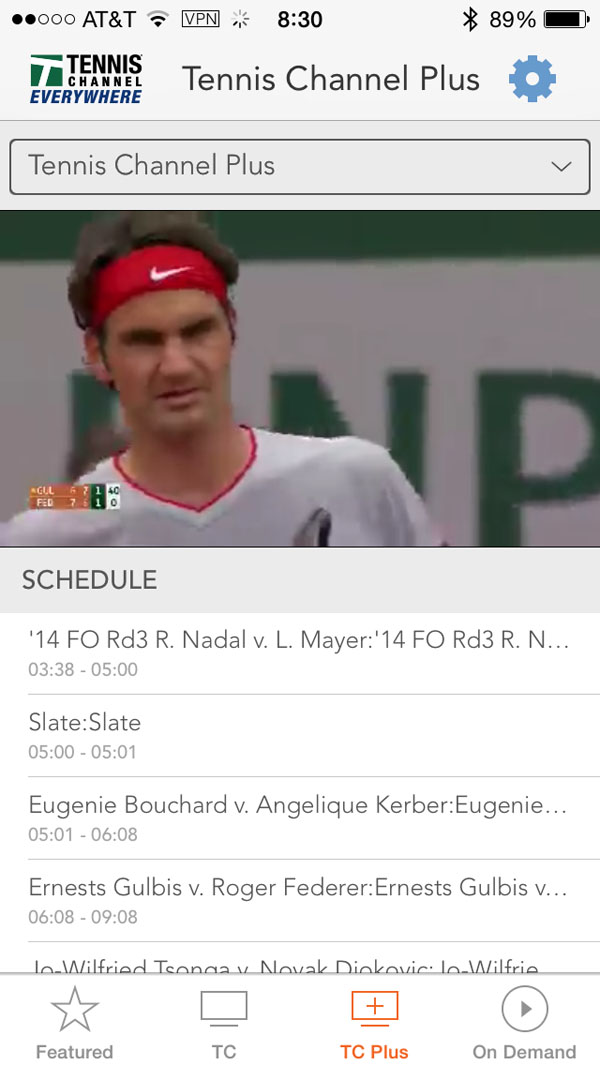

My last resort: the Tennis Television App. I tried it last year and learned that the world stands still. The Tennis Television app streams a portion of certain events ($59.99 in app purchase) while “WatchESPN” offers others. Both are pre-empted by “major” networks acquiring what appear to be exclusive rights for certain matches and/or time windows.

This user experience pain reveals both an opportunity and a major challenge for anyone trying to improve the tv experience. Byzantine rights and an obvious thick legacy infrastructure make change rare. Further, the WatchESPN app is “sandboxed”, that is it requires users to “authenticate” via their cable provider.

Oh, the humanity.

I’ve wondered how Steve Jobs passing might affect Apple’s ability to cut deals for its TV initiative. His reality distortion field was a well known asset when schmoozing others from Ross Perot to music industry players. *

My Saturday French Open app odyssey informs us that big opportunities remain, but much difficult deal making lies ahead. Might Apple’s new players be up to the challenge?

* I remain somewhat surprised that Apple has been unable to cut an interesting deal with Disney for ESPN. Jobs’ estate is a significant shareholder via the sale of Pixar to Walt’s Company in 2006.

Financial Hazards of the Fugitive Life

You may think of being on the run as a quandary for only a small group of recalcitrant, hardened criminals. But in her study of one Philadelphia neighborhood, Professor Goffman shows that it is a common way of life for many nonviolent Americans. These people often face charges related to possession or sale of small amounts of drugs, or offenses like hiding relatives from the law. Whatever the negative moral implications of such crimes, they don’t merit having one’s life ruined.

A core point of “On the Run” is that “young men’s compromised legal status transforms the basic institutions of work, friendship and family into a net of entrapment.” For instance, the police round up fugitives by monitoring and contacting their relatives — and that frays family relations. A young man might avoid showing up at the hospital to witness the birth of his child because he knows he could be caught or turned in. Family gatherings become another hazard, so in-person appearances are often surprise visits. People stuck in this kind of limbo are also reluctant to visit hospitals when they need treatment, and a result, the book says, is a “lifestyle of secrecy and evasion,” driven by the unfavorable incentives set in motion by the law.

Why IBM Is In Decline

It’s been a striking week for IBM. In its June 2014 issue, Harvard Business Review (HBR) published an interview with IBM’s former CEO Sam Palmisano, in which describes how he triumphantly “managed” investors and induced IBM’s share price to soar.

But IBM also made it to the front cover of Bloomberg Businessweek (BW) with a devastating article: “The Trouble With IBM.” According to BW, Palmisano handed over to his unfortunate successor CEO, Ginni Rometty, a firm with a toxic mix of unsustainable policies.

The key to Palmisano’s success in “managing” investors at IBM was—and is–“RoadMap 2015”, which promises a doubling of the earnings per share by 2015. The Roadmap is what induced Warren Buffett to invest more than $10 billion in IBM in 2011, along with many other investors, who were impressed with the methodical way in which IBM was able to make money. (Buffett’s investment was striking because of his long-standing and publicly announced aversion to investing in technology, which he confessed he didn’t understand.)

After all, IBM under Palmisano had doubled earnings per share in Roadmap 2010, and now it is “on track” to do the same by 2015 under the leadership of Ginni Rometty, another long-time IBMer, who took over as CEO in 2012. She has embraced the Roadmap with as much gusto as her predecessor.

Yet for critics of IBM like BW, “Roadmap 2015” is precisely what is killing IBM. According to BW, IBM’s soaring earnings per share and its share price are built on a foundation of declining revenues, capability-crippling offshoring, fading technical competence, sagging staff morale, debt-financed share buybacks, non-standard accounting practices, tax-reduction gadgets, a debt-equity ratio of around 174 percent, a broken business model and a flawed forward strategy.

The ‘Great Wave’ that reached the West

Ukiyo-e prints could be found in Europe from at least 1795 at the Cabinet des Estampes at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. It was not until the 1850s, however, when trade between Japan and Europe began to flourish, that the craze for things Japanese began to crescendo.

The story goes that French printmaker Felix Bracquemond (1833-1914) encountered a picture-book by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) that arrived in France with a shipment of porcelain in the late 1850s. In 1859, a sourcebook by the potter and designer Eugene Collinot and Adalbert de Beaumont included Hokusai’s imagery.

By the early 1860s, French intellectuals such as Charles Baudelaire and Edmond de Goncourt began to take interest. And that most internationally recognizable Hokusai print, commonly called the “Great Wave,” has now come to stand allusively for the surge of European interest in Japanese printmaking that emerged from the latter half of the 19th century.