Remember traffic. It was only 30 years ago that people were complaining about getting stuck in traffic. But traffic peaked in the early part of the Century, and has fallen ever since. A few observers picked this up early, but many transportation agencies were in denial.

At the time, most analysts saw only two possible futures:

Future 1: Per capita vehicle travel resumes an upward path. This forecast was the proverbial ostrich with its sand-encased head.

Future 2: Per capita vehicle travel remains flat but traffic grows with population. Future 2 was already causing concerns as it created pressures on revenues (which were then dependent on falling gas tax revenue), yet DOTs still claimed needs for new construction and expansion of existing roadways despite overall falling demand. Some argued that though demand was falling on average, it wasn’t mean it is falling everywhere. And there were still unsolved problems that don’t go away just because travel isn’t increasing.

No one in power foresaw what actually happened.

Future 3: Per capita vehicle travel falls significantly.

At first people attributed this to the Great Recession of the late Bush Presidency, but the evidence was that travel began dropping before the economy tanked. Technology restructured personal travel the way it completely devastated many other industries (remember newspapers, the post office, buying records and paper books, your land-line phone, canals, long distance passenger trains, broadcast television, electric utilities, going to College). Just look at this picture of demand for mail:

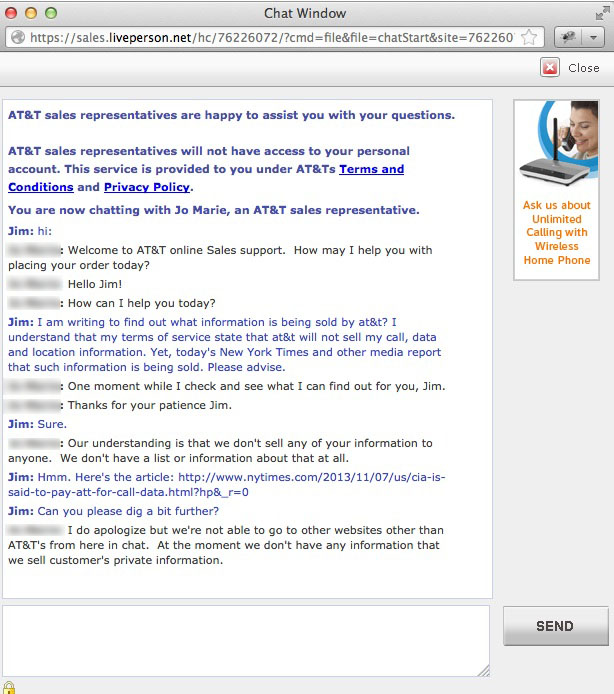

A Brief Chat with AT&T on Selling My Data

In light of Charlie Savage’s article on AT&T monetizing their user data, I asked “ma bell” about their data practices. A transcript follows:

Concert as an App: Fink & The Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra App. Delightful

The App Store.

Startup Idea: Used Car Leasing

Applications that open up spare capacity are a big deal. First eBay did it with the spare capacity of stuff in your attic. When counting pro sellers, eBay is the largest employer in the world. Next Airbnb took the spare capacity of your spare bedroom and turned it into the largest hotel in the world.

Cars could be next. There are ride sharing services, but they are modeled after Zipcars. That pattern works well for cities where driving is rare. For me, driving is extremely regular: get the kids to school, go to work, get groceries, etc. Getting a Zipcar daily doesn’t make sense, so the car sharing equivalents don’t either.

The model that does make sense is leasing, but leasing today stinks. First you have dealerships. Whether buying a new car, buying a used car, selling a used car, or leasing a new car, negotiating stinks, and it takes an actuary to figure out an optimal outcome. Selling a car on Craigslist is really cumbersome too, and Craigslist does nothing to smooth the transaction.

What If We Never Run Out of Oil?

As the great research ship Chikyu left Shimizu in January to mine the explosive ice beneath the Philippine Sea, chances are good that not one of the scientists aboard realized they might be closing the door on Winston Churchill’s world. Their lack of knowledge is unsurprising; beyond the ranks of petroleum-industry historians, Churchill’s outsize role in the history of energy is insufficiently appreciated.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911. With characteristic vigor and verve, he set about modernizing the Royal Navy, jewel of the empire. The revamped fleet, he proclaimed, should be fueled with oil, rather than coal—a decision that continues to reverberate in the present. Burning a pound of fuel oil produces about twice as much energy as burning a pound of coal. Because of this greater energy density, oil could push ships faster and farther than coal could.

Churchill’s proposal led to emphatic dispute. The United Kingdom had lots of coal but next to no oil. At the time, the United States produced almost two-thirds of the world’s petroleum; Russia produced another fifth. Both were allies of Great Britain. Nonetheless, Whitehall was uneasy about the prospect of the Navy’s falling under the thumb of foreign entities, even if friendly. The solution, Churchill told Parliament in 1913, was for Britons to become “the owners, or at any rate, the controllers at the source of at least a proportion of the supply of natural oil which we require.” Spurred by the Admiralty, the U.K. soon bought 51 percent of what is now British Petroleum, which had rights to oil “at the source”: Iran (then known as Persia). The concessions’ terms were so unpopular in Iran that they helped spark a revolution. London worked to suppress it. Then, to prevent further disruptions, Britain enmeshed itself ever more deeply in the Middle East, working to install new shahs in Iran and carve Iraq out of the collapsing Ottoman Empire.

Ur Turn: Getting My First Driver’s License At 25

I’m sitting at my desk, waiting for students to arrive and thinking about cars. Waking up at 6:00 on a Sunday morning is rarely fun, but I truly love what I do for a living. My fingers are stained from last night’s dye job, and they clutch a tall Styrofoam cup of hot chocolate. Together with a calorie-laden croissant, it’s a breakfast of champions that fuels my discussions as a teacher.

I filled the tank in my brother’s old Focus wagon a few weeks ago, spending what was small fortune to me to repay a favor of his. That car isn’t in great shape, but I borrow it whenever circumstances allow. It takes me to meetings, on errands, and through excursions with my darling nephew. It’s a rare moment that doesn’t see me begging to get behind the wheel, even if I’m only going to be driving for ten minutes.

Last year, I was a scared kitten. It was a few hours before Rosh HaShana and I had to merge onto the interstate for the first time. The driving instructor, a comedic sort, told me I should pray for a sweet new year. I just wanted to survive the freeway.

Google cars versus public transit: the US’s problem with public goods

I have an excellent job at a great university. I have a home that I love in a community I’ve lived in for two decades where I have deep ties of family and friendship. Unfortunately, that university and that hometown are about 250 kilometers from one another. And so, I’ve become an extreme commuter, traveling three or four hours each way once or twice a week so I can spend time with my students 3-4 days a week and with my wife and young son the rest of the time.

America is a commuter culture. Averaged out over a week, my commute is near the median American experience. Spend forty minutes driving each way to your job and you’ve got a longer commute than I in the weeks I make one trip to Cambridge. But, of course, I don’t get to go home every night. I stay two to three nights a week at a bed and breakfast in Cambridge, where my “ludicrously frequent guest” status gets me a break on a room. I spend less this way than I did my first year at MIT, when I rented an apartment that I never used on weekends or during school vacations.

This is not how I would choose to live if I could bend space and time, and I spend a decent amount of time trying to optimise my travel through audiobooks, podcasts, and phone calls made while driving. I also gripe about the commute probably far too often to my friends, who are considerate if not entirely sympathetic. (It’s hard to be sympathetic to a guy who has the job he wants, lives in a beautiful place, and simply has a long drive a few times a week.)

Boris Sofman’s answer to Anki: How are Anki cars different from other toy cars? What are the robotic features?

Thank you for your question — this is a very important one.

The cars in Anki Drive are characters in a video game brought to life in the physical world.

Anki Drive cars are extremely different from other types of cars (plastic, RC, etc.). They are very complex and capable robotic systems that can bring the characters they represent to life in a way that has never been possible outside of a video game: with intelligence, personality, and true interaction. For the first time, you can play a game where whatever cars you don’t control come to life and are controlled by the AI, reacting autonomously to what you’re doing and what the other cars are doing. The have a lot of sensors, motors, and computation internally (50 MHz microcontroller in each car) to make this possible.

In terms of their capabilities, there are 3 key challenges of robotics that we had to solve to make Anki Drive, and the capabilities of the cars within, possible:

Positioning — every car needs to understand precisely where it is, and where the other cars are relative to it. To do this, each car scans its environment 500 times per second to know with exact precision where it is located on the track, and wirelessly communicates that back to the mobile devices running the game.

Reasoning — Once the cars know where they are, we use that information to make intelligent decisions and plans for the cars that are controlled by the game. We use mobile devices as the ‘brains’ behind the real-world game, thinking about thousands of potential actions every second for each car.

Prius + 10: Performance Is All That Matters

TOYOTA, RESTORED AS the world’s largest auto maker by sales in 2013, produces lots of amazing vehicles. It makes the world’s most durable small pickup, the Hilux. On the other side of the vehicular universe, there is the Lexus LFA, a carbon-bodied apparition with a naturally aspirated V10 engine and a spine-tingling 9,000 rpm redline. Me want.

Toyota 7203.TO -0.47% builds the best-selling sedan in America, the Camry; it builds full-size, steak-eating trucks in Texas (more than 1 million at last count). This company has bandwidth.

The Intergenerational Transmission of Automobile Brand Preferences: Empirical Evidence and Implications for Firm Strategy

Soren Anderson, Ryan Kellogg, James Sallee & Ashley Langer:

We document a strong correlation in the brand of automobile chosen by parents and their adult children, using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. In our preferred estimates, children are 46% more likely to choose an automobile brand if their parents also chose that brand. Correlation in intrafamily brand choice could represent a causal trans- mission of brand preference, or it could be due to correlated family characteristics that determine brand choice. We present a variety of empirical specifications that lend support to the causal interpretation. We then discuss implications of intergenerational brand pref- erence transmission for automakers and market outcomes, focusing on a model of Bertrand competition in the presence of brand loyalty that is transmitted across generations. We find that intergenerational transmission of brand preferences should lower equilibrium prices for vehicles targeted at parents and raise equilibrium prices for vehicles targeted at children. We further show that firms have a unilateral incentive to instill a sense of brand loyalty in their consumers, even though equilibrium profits may decrease when all firms do so.