JB: Sounds like it’s a big deal, but fast Internet and slow Internet, those can be abstract ideas so lay things out for me clearly: what can people do in Tullahoma that they can’t do in other parts of the state?

AH: In Tullahoma, there’s a small startup software company called Agisent, it actually moved from South Carolina to Tullahoma because Tullahoma’s very fast, it’s a gigabit network, one of the fastest in the world. For a town of 18,000 that’s pretty impressive. And also it’s very reliable and that’s what this company called Agisent needs. What they do is they provide a web document management service to police departments, prisons, courts typically; they are small to medium sized departments that can’t afford their own IT expert to manage their networks so that’s really important to them that they can do that in Tullahoma.

That’s fine for Agisent. But then you go outside of Tullahoma, you just drive like 3, 4, 5 miles outside of Tullahoma into this suburban area where there are some very nice homes, and they don’t have Internet access. They don’t even have AT&T, U-verse or Charter Communications which is another telecom there who provides service in Tullahoma. They don’t serve this area. And ran into a fellow named Matt Johnson, he is an entrepreneur, he started up a company called Road Rage Gauges, which are gauges that you put in your truck or high performance car to measure how it’s performing so you don’t overtax your engine or damage it in some way. What he did was he spent $2,000 rigging up a system so that he could get wireless access, but that’s just way too slow for him. He has clients in China and South Africa and Germany that he has to talk to and when we visited him at his home, this is what he told us about his experience:

Get ready for companies that run themselves.

Imagine, for instance, a bike-rental system administered by a DAC hosted across hundreds or thousands of different computers in its home city. The DAC would handle the day-to-day management of bikes and payments, following parameters laid down by a group of founders. Those hosting the management programme would be paid in the system’s own cryptocurrency – let’s call it BikeCoin. That currency could be used to rent bikes – in fact, it would be required to, and would derive its value on exchanges such as BitShares from the demand for local bike rentals.

Guided by its management protocols, our bike DAC would use its revenue to pay for repairs and other upkeep. It could use online information to find the right people for various maintenance tasks, and to evaluate their performance. A sufficiently advanced system could choose locations for new stations based on analysis of traffic information, and then make the arrangements to have them built.

One of the most intriguing parts of such a system is that it allows the crowdfunding of large-scale projects without the centralisation and fees of either stock exchanges or platforms such as Kickstarter. The DAC platforms themselves are models – in the year since Bitcoin Miami, Ethereum has raised about $14 million, and BitShares around $6 million, solely through the direct sale of the digital currency that will allow people to run programs or make exchanges on their networks.

The German Moment in a Fragile World

“Germany is Weltmeister,” or world champion, wrote Roger Cohen in his July 2014 New York Times column1—and he meant much more than just the immediate euphoria following Germany’s first soccer world championship since the summer of unification in 1990. Fifteen years earlier, in the summer of 1999, the Economist magazine’s title story depicted Germany as the “Sick Man of the Euro.”2 Analysis after analysis piled onto the pessimism: supposedly sclerotic, its machines were of high quality but too expensive to sell in a world of multiplying competitors and low-wage manufacturing. Germany seemed a hopeless case, a country stuck in the 20th century with a blocked society that had not adapted to the new world of the 21st century, or worse, a society that was not even adaptable.

Things since then have changed significantly. In the summer of 2013, more than a year before the triumph in Rio de Janeiro, the Economist reversed its own verdict—Germany now appeared on the front page as “Europe’s Reluctant Hegemon.”3 In 2014, Germany came out on top for the second year in a row in the BBC’s annual country rating poll as the country with “the most positive influence on the world.”4 Simon Anholt’s annual “Nation Brand Index” also put Germany in the top spot in 2014.5

Chicken & Prayer

It’s always the chicken, except when it is the salad.

Years ago, while waiting for a long delayed flight in Juarez, a kind local physician took my roommate and I to dinner before we departed for Mazatlan. My roommate dealt with “Montezuma’s Revenge” in flight. Mine arrived a bit later, after midnight in our pleasant tiny motel.

That next day, while relaxing and recovering, I reflected on what might have caused our unpleasantness. It must have been the chicken.

Fifteen years later, in Anchorage, Nancy and I dined at Wendy’s – the salad bar. Later that night, Montezuma returned. A visit made doubly worse by the early morning train ride north to Denali. The train seemed to sway more than expected, made worse by a New Jersey seatmate who kindly offered stock tips for the duration.

“AT&T. Buy it and forget about it. General Motors, buy it and forget about it. Berkshire Hathaway. Buy it and forget about it.”

Two out of three is not bad.

And so it was, two decades later, Montezuma returned during a visit to Mexico. I must admit that the experience was far worse than I remembered.

Pollo.

Always the chicken.

The Bohemia “cerveza fria” – drank just before Montezuma arrived – made the experience that much worse.

I remember being very light headed and praying for relief. Suddenly, I felt much better. A miracle during the worse food poisoning I’ve experienced.

I pray and hope that it never occurs again. We have yet to try another pollo meal.

“With increasing frequency, strongly held regional interests outstrip the commitments of more powerful global actors, more often retrenching. This asymmetry of interests can make conflict resolution significantly more difficult. “

On the positive side, I would say that this new situation will over time create new opportunities, as multiple combinations of power should make the international system more flexible. More powers, in principle, can at least better carry the burden of an international order. This is not and should not be a world where you are ‘with us or against us’. This is a world in which regional organizations could at last take a greater role. So there are many positive elements to that world.

But what we see today is more the negative side of it, the negative dimension of true multipolarity and diffusion of power. Let me explain. With increasing frequency, strongly held regional interests outstrip the commitments of more powerful global actors, more often retrenching. This asymmetry of interests can make conflict resolution significantly more difficult. The resolution of the Syrian conflict is made all the more difficult as regional divisions are added to the global divisions, and that is not a unique situation. Neighbouring states, of course, in any conflict need to be brought along, because of their first- hand expertise, because it’s their immediate security and economic interests that are most endangered by conflict next door. But they can become obstacles to peace. Look at Somalia, now effectively carved into spheres of influence. Look at South Sudan, where leaving the political track to IGAD alone – IGAD is very important in South Sudan, but it can’t do it all alone. Leaving the political track to IGAD alone is simply not working. Look at the regionally manned force intervention brigade in the DRC, where some regional tensions are appearing. So regional engagement is necessary but it can, if not well managed, deepen regional rivalries.

This is why Pettis thinks Varoufakis’s plan to swap existing Greek debts for obligations indexed to GDP is a good idea that ought to be expanded to other countries, including Spain and Italy. The appeal of these GDP-indexed obligations is that they give creditors an incentive to support investments in future growth.

That’s very different from the current setup, where the Troika has every incentive to tie its funding to the willingness to implement austerity programmes. Even if those programmes boosted productivity in the long term by shifting resources away from the state, the behaviour demanded by the euro area’s official sector creditors exacerbates the cyclical weakness.

The good news, though, is that a different liability structure that encourages additional investment could instantly lead to stronger growth given the reforms that have already occurred. Moreover, a large-scale restructuring should encourage lots of new investment even if it also wipes out many existing creditors, at least if they are done soon. As Pettis puts it:

Location:Michael Pettis explains the euro crisis (and a lot of other things, too)

My People, Under The Bombs

DOUMA, Syria, February 6, 2015 – It’s an airstrike that wakes me up, just near my house in a rebel-held part of the Damascus suburbs. It’s 8.30 am. I think at first it’s just the one, but my hopes soon fade with the sound of another strike. And another.

The bombing doesn’t stop until sunset. The government jets target everything. Apartment blocks, mosques, schools, even a hospital. The assault is in reprisal for a major rebel attack that left 10 dead in the capital the day before. As I have taken to doing in such cases, I head down to the makeshift clinic, where I witness the most awful scenes you could imagine.

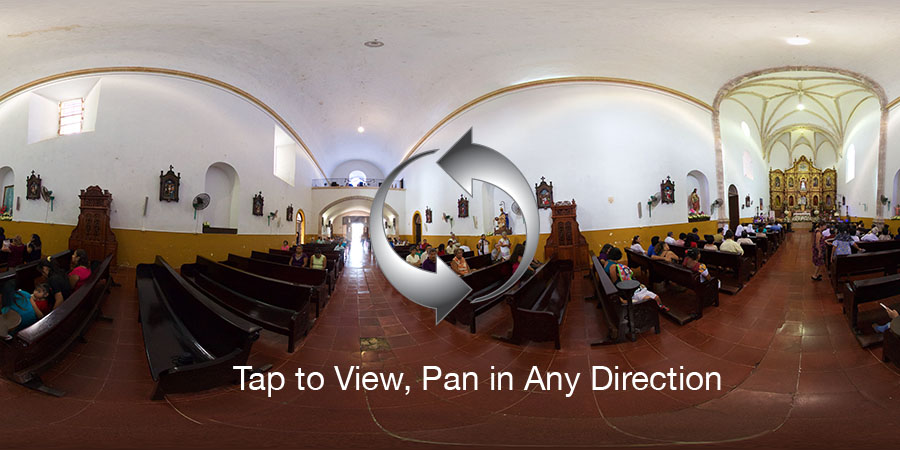

Izamal Monastery Photos & Panoramas

Worth a visit.

Learn more about Izamal via wikipedia and Lonely Planet.

Hotel Santo Domingo is sublime.

Snow Scenes Madison 1 February 2015

Hipster churches in Silicon Valley: evangelicalism’s unlikely new home

Like many San Franciscans, overpriced coffee is a considerable portion of my weekly budget. One day in Soma, the industrial district home to many start-ups, I came across a flier advertising a free gift card to Philz, a nearby coffee shop. All that was required was to show up for service at a local church called Epic. I hadn’t been to church in months, and decided to give it a try.

The Bay Area has never been perceived as religious: a 2012 Gallup poll found that fewer than a quarter of residents identify as “very religious” (defined as going to church weekly), as opposed to 40% of the nation as a whole. High salaries have drawn droves of well-educated millennials to the booming tech sector, which correlates with lower religious sentiment. So far afield from the Bible belt, the region is in fact seen as hospitable to all forms of old testament abominations: fornication, paganism – even sodomy.