He said, “Well, you have to understand, it was never depressing. Because despite all those circumstances, I never ever wavered in my absolute faith that not only would I prevail—get out of this—but I would also prevail by turning it into the defining event of my life that would make me a stronger and better person. Not only that, Jim, you realize I’m the lucky one.”

I said, “No, I don’t.”

He said, “Yes, because I know the answer to how I would do, and you never will.”

A little later in the conversation, after I’d absorbed that and said nothing for about five minutes because I was just stunned, I asked him who didn’t make it out of those systemic circumstances as well as he had.

He said, “Oh, it’s easy. I can tell you who didn’t make it out. It was the optimists.”

And I said, “I’m really confused, Admiral Stockdale.”

A Storm for Which We Were Unprepared (2005)

I am a physician and a surgeon who by accident of fate finds himself in the halls of power at a time of dangers for his country and the world, the most compelling of which are exactly those a physician is trained to recognize and fight. To me it seems no more natural to be a United States senator, and in my case the majority leader of the Senate, than it did to Harry Truman, who spent so many hard and unambitious years as a farmer and then found himself in such a place and at such a time as he did. And, like him, as someone who comes from the outside, and for whom the perquisites of power appear strange and irrelevant, I have asked myself what my purpose is as a public servant, what my obligations are, and what high precedents I should follow.

After some thought, I have determined my purpose, I know my duty and obligations, the precedents to honor, and why—neither history nor life itself being empty of example. Just as a surgeon must follow a purely objective course and a general must look at war with a cold and steady eye, a statesman must operate as if the world were free of emotion. And yet, to rise properly to the occasion, the surgeon must have the deepest compassion for his patient, the general must have the heart of an infantryman, and the statesman must know at every moment that the cost of his decisions is borne, often painfully, by the sovereign population he serves—all as if the world were nothing but emotion. The difficulty in this is what Churchill called the “continual stress of soul,” the rack upon which the adherents of these professions, if they meet their obligations well, will of necessity be broken.

In balancing objectivity with emotion, the practical with the moral, the smooth operation of power with its homely and human effects, one is driven to consider first things and elemental purposes, and this consideration makes clear that the guiding star of statesmanship is not aggrandizement of the state or the furtherance of a philosophy or ideology, and neither glory nor ambition nor accumulation of territory or riches. Rather, the guiding star must be the fact of human mortality, and the first purpose of a public official a simple watch upon the walls. We are charged above all with assuring the survival of the nation and protecting the lives of those whom we serve and who have put us in our place, entrusting us with this gravest of responsibilities.

Whether leading a small nomadic band, captaining a ship, or at the head of a huge industrial nation, the task is the same. It is not merely that which can be accomplished with sword and shield, but, rather, the exercise of courage, sacrifice, and judgement, in the preservation of the life of a nation in its people as families and individuals. And as if by design, this task becomes in its execution a principle that unites the powerless and powerful in an unimpeachable equality.

I Spent Seven Weeks in a Wuhan ICU. Here’s What I Learned

It was late at night on Jan. 24, the day after Wuhan went into lockdown, when I boarded a plane bound for the city as part of a 128-member medical support team sent from the southern Guangdong province to the epicenter of China’s COVID-19 epidemic. We received a brief training session the next day, and on Jan. 26, we were taken to the hospital ward where we would spend the next 54 days.

I’ve been a doctor in an intensive care unit for 12 years, and during that time I’ve dealt with all manner of serious diseases. But stepping into that ward was the most terrifying moment of my life.

The cleaning staff and security guards hired by the hospital — most of them contractors — were gone, and the hallways were covered in garbage bags and contaminated medical waste. The ward was staffed by a total of two ophthalmologists and two nurses who were expected to care for 85 critically ill patients in varying degrees of respiratory distress.

Most of these patients should have been in an ICU, not a converted inpatient clinic. That first day, we watched as one of the doctors did their best to save a patient near death. It was no use: The hospital didn’t have enough oxygen left.

How People Read Online: New and Old Findings

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

We recently published the 2nd edition of our How People Read Online report, almost 15 years after the 1stedition was published. Looking back over the findings from the 5 eyetracking studies conducted for these editions, we can trace how online reading behaviors have changed (or not).

We’ve been saying this since 1997: People rarely read online — they’re far more likely to scan than read word for word. That’s one fundamental truth of online information-seeking behavior that hasn’t changed in 23 years and which has substantial implications for how we create digital content.

The reason why that finding (and others discussed here) is still true is because it’s based on basic human behavior. Even though massive technology shifts have changed some behaviors, many of our original findings about how people read online remain true, even after 20+ years.

Methodology: Eyetracking

Methodology: Eyetracking

Eyetracking equipment tracks a user’s gaze as she uses an interface. This type of research is valuable for many purposes (including evaluating visual design), but is particularly useful for studying what people do (and don’t) read online.

Most of the studies discussed below contained both a quantitative and a qualitative portion:

California Water Consumption and Midwest Farming

I’ve been reading Mark Arax’s terrific book: The Dreamt Land.

A former resident and frequent visitor, I’ve long found California to be a fascinating place.

Arax chronicles the posturing, economics, environmental cost and special interests behind Golden State water policies and practices:

On the ground, it’s hard to get a fix on the Central Valley; it flashes by as dun-colored monotony — a sun-stunned void beyond the freeway berms. The view from the air is clarifying, then. Aloft, the landscape resolves itself into a semblance of order: sterile and abstract — a frieze of clean lines, hard angles, swatches of green and brown, and pane-like water features. For many Angelenos, it’s just that: flyover territory. But in “The Dreamt Land,” former L.A. Times reporter Mark Arax makes a riveting case that this expanse — 450 miles lengthwise from Shasta to Tehachapi; 60 miles across from the Sierra Nevada to the Coastal Range — as much as the world cities on its coast, holds the key to understanding California.

The wide-angle view is of a land transfigured by the human hand — its waterways dammed, diverted, even reversed to quench thousands of otherwise-arid acres, themselves scoured and graded. “The valley in its natural state resembled a rolling savanna not unlike the Serengeti,” writes Arax. Today, it stands primped for agricultural production — a project unparalleled globally. But if it’s no less man-made than the concrete canyons of Los Angeles and San Francisco, it’s also revealed here to be as much a crucible of mammon — the playground of outsize personalities as hard-bitten as the hardpan they pinned their fortunes on, and locus for epic feuds and dastardly schemes.

The crazy water consumption practices have made me wonder if the end is nigh for California’s agricultural bounty. And, what that might mean for Midwest farmers.

Well worth reading.

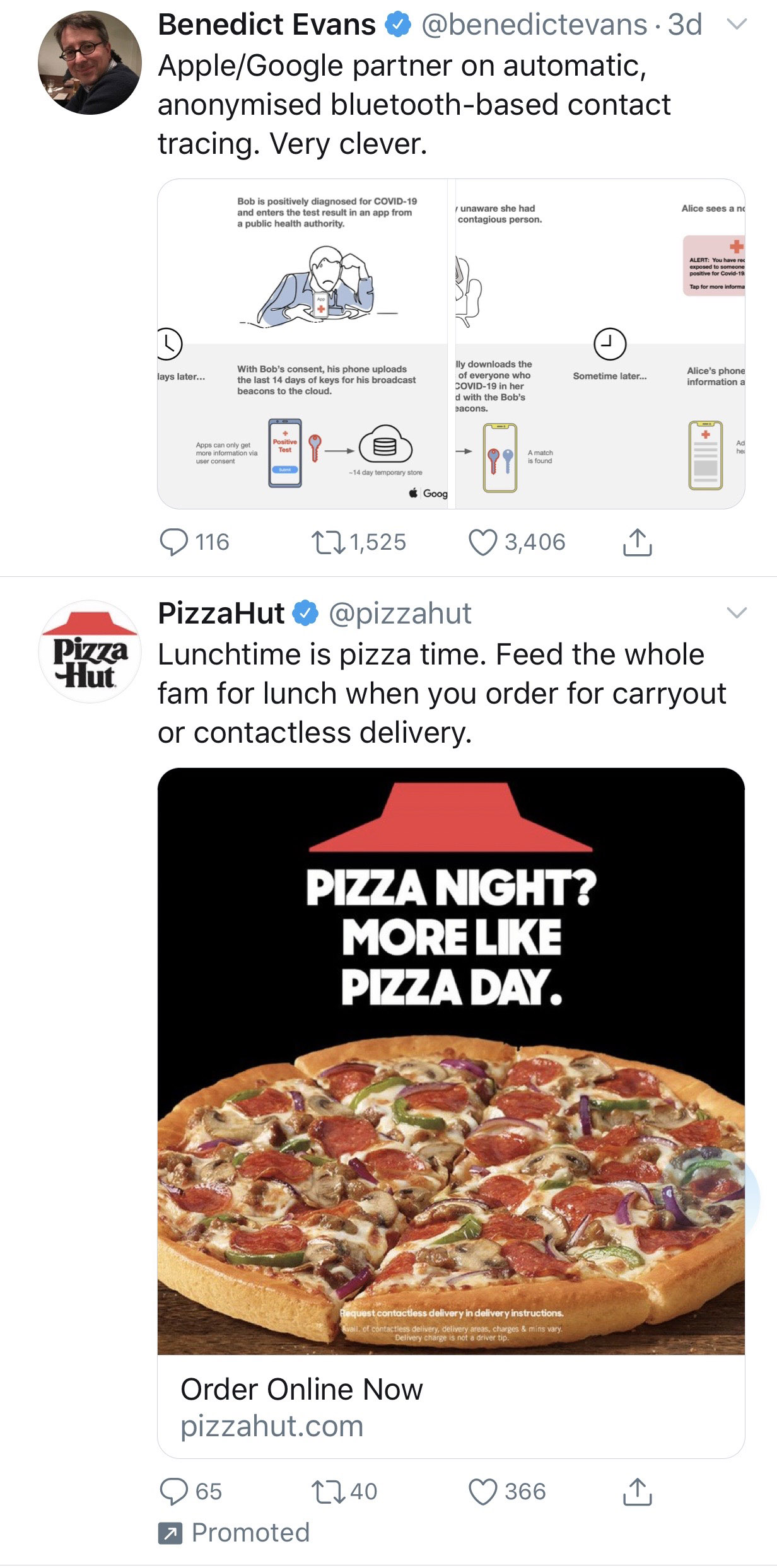

2020, so far; Bluetooth “Contact Tracing”

Pizza Hut….

[Time to check your iPhone/iPads: Settings > Privacy > Bluetooth. Likely best to turn them all off, particularly Facebook]

Apple and Google announced “Privacy-Preserving Contact Tracing“.

Apple and Google’s engineering teams have banded together to create a decentralized contact tracing tool that will help individuals determine whether they have been exposed to someone with COVID-19.

Contact tracing is a useful tool that helps public health authorities track the spread of the disease and inform the potentially exposed so that they can get tested. It does this by identifying and “following up with” people who have come into contact with a COVID-19-affected person.

The first phase of the project is an API that public health agencies can integrate into their own apps. The next phase is a system-level contact tracing system that will work across iOS and Android devices on an opt-in basis.

We call on all governments not to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic with increased digital surveillance unless the following conditions are met:

Surveillance measures adopted to address the pandemic must be lawful, necessary and proportionate. They must be provided for by law and must be justified by legitimate public health objectives, as determined by the appropriate public health authorities, and be proportionate to those needs. Governments must be transparent about the measures they are taking so that they can be scrutinized and if appropriate later modified, retracted, or overturned. We cannot allow the COVID-19 pandemic to serve as an excuse for indiscriminate mass surveillance.

If governments expand monitoring and surveillance powers then such powers must be time-bound, and only continue for as long as necessary to address the current pandemic. We cannot allow the COVID-19 pandemic to serve as an excuse for indefinite surveillance.

States must ensure that increased collection, retention, and aggregation of personal data, including health data, is only used for the purposes of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collected, retained, and aggregated to respond to the pandemic must be limited in scope, time-bound in relation to the pandemic and must not be used for commercial or any other purposes. We cannot allow the COVID-19 pandemic to serve as an excuse to gut individual’s right to privacy.

Governments must take every effort to protect people’s data, including ensuring sufficient security of any personal data collected and of any devices, applications, networks, or services involved in collection, transmission, processing, and storage. Any claims that data is anonymous must be based on evidence and supported with sufficient information regarding how it has been anonymized. We cannot allow attempts to respond to this pandemic to be used as justification for compromising people’s digital safety.

Any use of digital surveillance technologies in responding to COVID-19, including big data and artificial intelligence systems, must address the risk that these tools will facilitate discrimination and other rights abuses against racial minorities, people living in poverty, and other marginalized populations, whose needs and lived realities may be obscured or misrepresented in large datasets. We cannot allow the COVID-19 pandemic to further increase the gap in the enjoyment of human rights between different groups in society.

How Google Plans to Push Its Coronavirus Tracing Feature to Android Phones.

Campaigners call on broadcasters and streamers to seize the moment to switch on subtitles for kids’ programming

An urgent call is to go out to children’s television broadcasters this weekend, backed by major names in British entertainment, politics and technology. Writer and performer Stephen Fry, best-selling author Cressida Cowell and businesswoman Martha Lane Foxare joined by former children’s television presenter Floella Benjamin as signatories to a letter, carried in today’s Observer, that urges all leading streaming, network and terrestrial children’s channels to make one simple change to boost literacy among the young: turn on the subtitles.

If English-language subtitles were to be run along the bottom of the screen for all programming, they argue, reading levels across the country would automatically rise. Longstanding international academic research projects prove, they say, that spelling, grammar and vocabulary would all be enhanced, even if children watching TV are not aware they are learning.

The campaign aims to improve reading ability across the English-speaking world and has won backing from former President Bill Clinton, who said: “Same-language subtitling doubles the number of functional readers among primary school children. It’s a small thing that has a staggering impact on people’s lives.”

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

Contact Tracing in the Real World

There have recently been several proposalsfor pseudonymous contact tracing, including from Apple and Google. To both cryptographers and privacy advocates, this might seem the obvious way to protect public health and privacy at the same time. Meanwhile other cryptographers have been pointing out some of the flaws.

There are also real systems being built by governments. Singapore has already deployedand open-sourced one that uses contact tracing based on bluetooth beacons. Most of the academic and tech industry proposals follow this strategy, as the “obvious” way to tell who’s been within a few metres of you and for how long. The UK’s National Health Service is working on one too, and I’m one of a group of people being consulted on the privacy and security.

But contact tracing in the real world is not quite as many of the academic and industry proposals assume.

First, it isn’t anonymous. Covid-19 is a notifiable disease so a doctor who diagnoses you must inform the public health authorities, and if they have the bandwidth they call you and ask who you’ve been in contact with. They then call your contacts in turn. It’s not about consent or anonymity, so much as being persuasive and having a good bedside manner.