Delayed flights occur, perhaps, to remind us to relax and enjoy the moment.

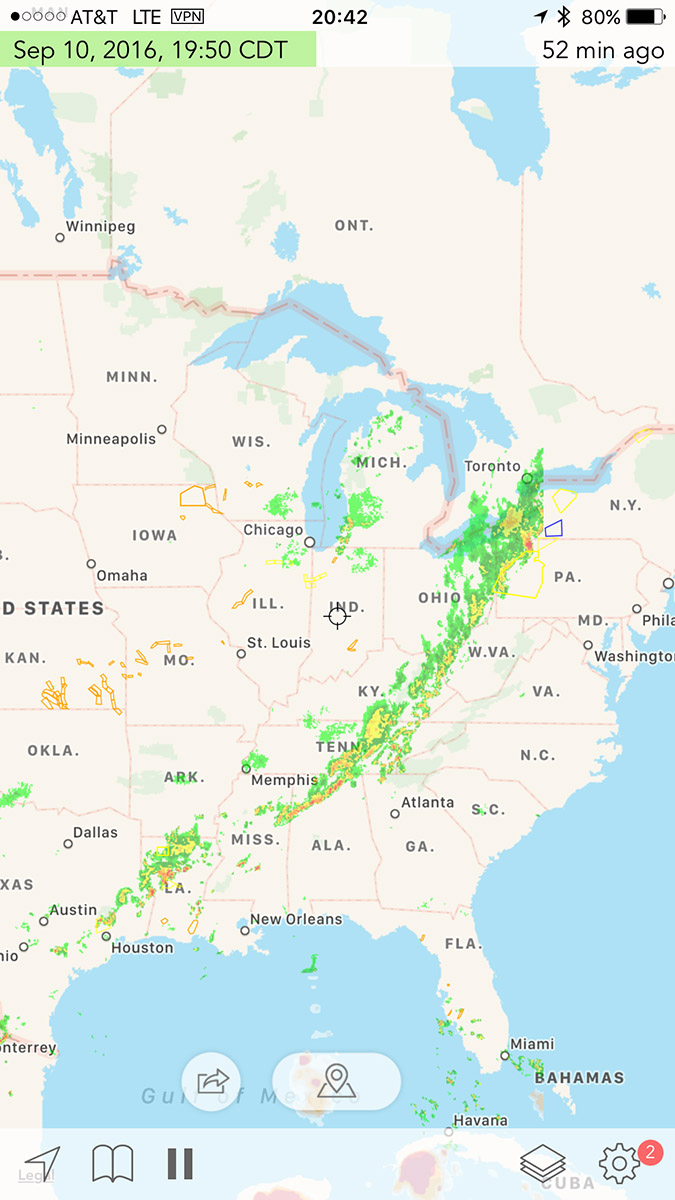

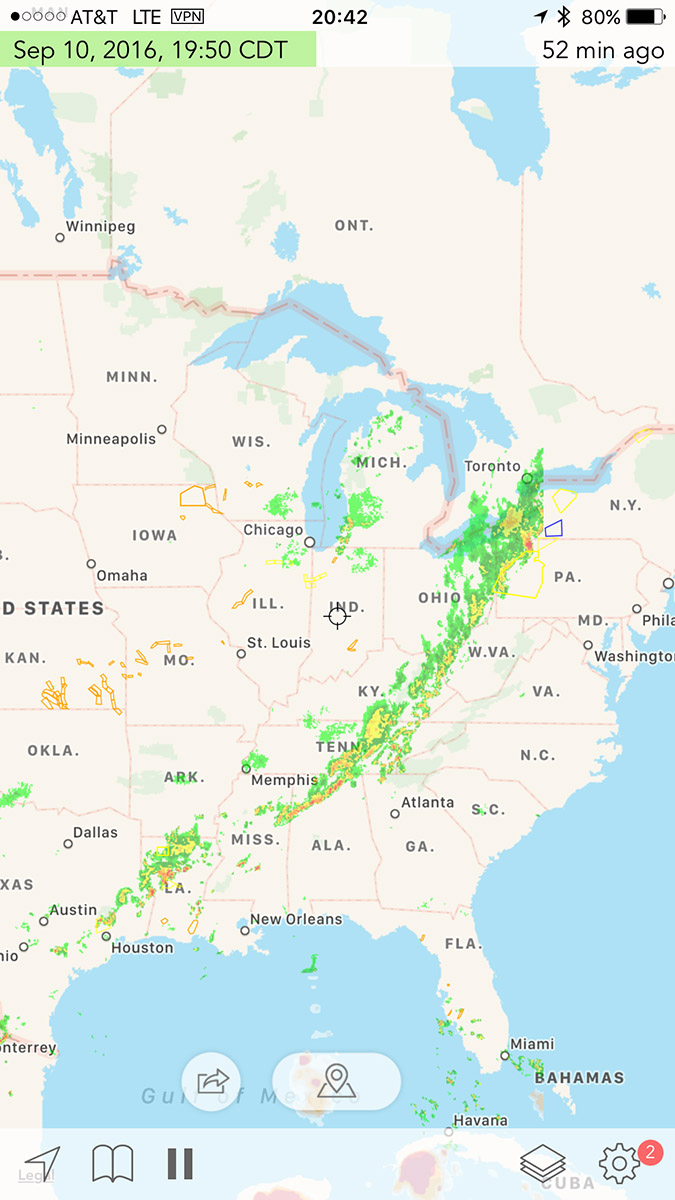

And, so it was while flying west, through a large line of thunderstorms, that gorgeous, sun soaked clouds appeared to my left.

Delayed flights occur, perhaps, to remind us to relax and enjoy the moment.

And, so it was while flying west, through a large line of thunderstorms, that gorgeous, sun soaked clouds appeared to my left.

Libreville — When I got to Gabon to cover the recent election, I found myself the only photographer from a major global news organization in the country. People ask — why bother covering yet another election and unrest in yet another African country? I tell them – how can we not? This is where Africa’s modern history is unfolding. If we are going to tell the story of Africa, of the narratives that are taking place on the continent, then we cannot back off from coming to places like these.

I take pride in the fact that I’m here and telling the story and that we’re not passing on these kind of events.

Occasionally, I have the privilege of meeting an international visitor to the United States. In some cases, it is their first visit. Perhaps, they are visiting my home – the Madison area.

I often mention three books that might provide a lens to contemplate the recent United States.

They are:

A. When Pride Still Mattered by David Maraniss,

B. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig, and

C. Lake Wobegon Days by Garrison Keillor.

There are surely many others.

If muckraker, journalistic impresario and scoundrel Warren Hinckle, who died last week at 77, is not getting the media sendoff befitting someone of his accomplishment and influence, he has nobody to blame but himself. The New York Times filed a lengthy obituary, and Hinckle’s hometown newspaper in San Francisco saluted him, but most of the nation’s other leading dailies gave his death a bye, which is a shame. There were a handful of appreciations in the left corners of the Web, yet none of them conveyed the force he exerted on journalism in his prime. He embraced the role of attack dog, formulated like this for a 1981 Washington Post profile: “What journalism is all about is to attack everybody,” he said after downing his fifth screwdriver. “First you decide what’s wrong, then you go out to find the facts to support that view, and then you generate enough controversy to attract attention.” The people who believe that the journalist should never be the story never met Warren Hinckle.

Hinckle mostly added footnotes to the art of journalism during the past 40 years, but during his prime, which ran from 1965 to 1975, he practiced journalism like a political insurrectionist, rushing into combat with one eye patched (from a childhood injury) and even sporting a cape on occasion. In his prime, he changed American journalism for good by creating Ramparts, which served as a media crawlspace for investigative reporters and culture critics in the 1960s. The magazine’s influence was immense: Its spirit was evident when the New York Times published the Pentagon Papers, and in 1968, when 60 Minutes got up and running; and it permeated Rolling Stone, launched in 1967 (and which the always acerbic Hinckle denounced as “counterculture bullshit”). The Ramparts lineage goes on: Mother Jones, which used the collapsed Ramparts as a kind of parts car; the alt-weeklies, which got started about the time that Ramparts died in 1975; and more recently sites like Gawker and the Intercept.

Here’s the thing. As vendors become more adept at increasing return on attention for their customers, their need to advertise is likely to diminish. If they are more and more helpful to their customers, word of mouth will spread among customers and they will flock to the vendors who can improve their return on attention. And, it won’t be just word of mouth among customers. On the product side, curators are likely to emerge to help customers sort through the ever expanding variety of products and services given deep expertise in certain categories of product and services. On the customer side, I have written about the emergence of trusted advisors who will invest in deeply understanding us as individual customers and become more and more helpful to us in recommending products or services we may not even have asked about.

With all of these resources to draw on, what is the value of conventional product advertising to the customer or to the vendor? It’s likely to diminish in importance. As I’ve written elsewhere, the power of pull will replace the diminishing power of push. We will see much more helpful forms of marketing evolve – an approach that I’ve called collaboration marketing. In this rapidly evolving world, companies that continue to rely on advertising as a business model are likely to experience growing pressure. Customers will gladly pay for the opportunity to increase return on attention and find ever more sophisticated ways to evade the classic push model of advertising.

This isn’t going to happen overnight. Companies have both the blessing of time and the curse of time. The blessing is that there is time to evolve and develop new business models. The curse is that, because this will not happen overnight, there is an understandable but very dangerous tendency to become complacent and not move aggressively enough to avoid the cliff ahead.

Topped off by a dozen ears of sweet corn for $3…

For centuries, the cost of distance has determined where businesses produce and sell, where employers locate jobs and where families choose to live, work, shop and play. What if this cost fell dramatically, thanks to new technologies? How would the global economy change if manufacturers could produce locally in small batches, without incur- ring excess cost? Would existing business models and supply chains, for instance, suddenly become uncompet- itive? If people could work from anywhere, would crowded neighborhoods start to thin out?

That change already has begun in the world’s advanced economies and is gathering momentum. Over the next two decades, the cost of distance will decline sharply, according to Bain research, altering the way we live and work—faster than most people expect and more broadly than many imagine. This next big economic shift will create an astonishing array of opportunities for businesses and investors—and unexpected risks.

The catalyst for this historic shift is an array of new platform technologies that have pushed the cost of distance to the tipping point. Multibillion-dollar investments in robotics, 3-D printing, delivery drones, logistics technology, autonomous vehicles and low-Earth-orbit (LEO) satellites are giving rise to new products and services that sharply erode the cost of moving people, goods and information. As these technologies combine and converge, change will accelerate.

For leaders steering companies through this transition, the change will feel turbulent and unfamiliar. Risks will multiply for industries of all kinds. As the very nature of growth shifts, some of the underlying assumptions of existing business models may no longer be valid, leaving many companies with assets stranded in the wrong locations or with businesses that are becoming obsolete.

Growth opportunities, in particular, will shift dramatically. Today’s high-growth emerging markets, the main focus of business investment for over a decade, are likely to struggle. In contrast, advanced economies will have the poten- tial to embark on a period of sustained expansion.

As we saw previously, Thiel was ruminating on Strauss, Schmitt, and Girard in the summer of 2004, but also on the future of social media platforms, which he found himself in a position to help shape. It is worth adding that around the same time, Thiel was involved in the founding of Palantir Technologies, a data analysis company whose main clients are the US Intelligence Community and Department of Defense – a company explicitly founded, according to Thiel, to forestall acts of destabilizing violence like 9/11. One may speculate that Thiel understood Facebook to serve a parallel function. According to his own account, he identified the new platform as a powerful conduit of mimetic desire. In Girard’s account, the original conduits of mimetic desire were religions, which channeled socially destructive, “profane” violence into sanctioned forms of socially consolidating violence. If the sacrificial and juridical superstructures designed to contain violence had reached their limits, Thiel seemed to understand social media as a new, technological means to achieving comparable ends.

If we take Girard’s mimetic theory seriously, the consequences for the way we think about social media are potentially profound. For one, it would lead us to conclude that social media platforms, by channeling mimetic desire, also serve as conduits of the violence that goes along with it. That, in turn, would suggest that abuse, harassment, and bullying – the various forms of scapegoating that have become depressing constants of online behavior – are features, not bugs: the platforms’ basic social architecture, by concentrating mimetic behavior, also stokes the tendencies toward envy, rivalry, and hatred of the Other that feed online violence. From Thiel’s perspective, we may speculate, this means that those who operate those platforms are in the position to harness and manipulate the most powerful and potentially destabilizing forces in human social life – and most remarkably, to derive profits from them. For someone overtly concerned about the threat posed by such forces to those in positions of power, a crucial advantage would seem to lie in the possibility of deflecting violence away from the prominent figures who are the most obvious potential targets of popular ressentiment, and into internecine conflict with other users.