George Steinmetz‘s new exhibition and book, Desert Air, is the first comprehensive photographic collection of the world’s “extreme deserts”, which receive less than four inches of precipitation a year. This body of work, culled from 15 years of shooting, takes the viewer from China’s Gobi Desert to the Sahara in northern Africa to Death Valley in California.

Steinmetz photographs from a motorized paraglider which he describes as a “flying lawn chair”. Using the slowest and quietest powered aircraft in the world, he is not only able to take off and land without an airfield or government permission but is also likely to land in someone’s yard and be invited in for tea, becoming the talk of the town.

In his thirty year career, Steinmetz has been a regular contributor to National Geographic and GEO magazines and has won numerous awards including two first prizes in science and technology from World Press Photo. Desert Air will be on view through March 3, 2013 at Anastasia Photo.

Sandy inspires first Doctors Without Borders U.S. relief effort

NEW YORK, Nov 8 (Reuters) – Manhattan doctor Lucy Doyle has done stints with the global medical relief organization Doctors Without Borders in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Kenya. But her latest assignment is a real eye-opener: New York City.

In the wake of Superstorm Sandy, Doctors Without Borders has set up its first-ever medical clinic in the United States, and Doyle finds herself on the front line of disaster just miles from her day job.

“A lot of us have said it feels a lot like being in the field in a foreign country,” said Doyle, who specializes in internal medicine at New York’s Bellevue Hospital, now closed by Sandy’s damage.

Is apathy the new black death?

I live in Spain and seriously, nearly all if not all the people I meet lack enthusiasm, are generally lethargic and display signs of an acute aversion towards work and effort in general, not to speak of suffering. On the other hand, everybody’s going to demonstrations and protesting and complaining about everything, but generally doing nothing in the long term because that means hard work. This is seriously wearing me down. I’ve met along the years amazingly talented people that just want to do nothing, and I wonder if it is possible at all for me to do everything always alone while drowning in this apathetic pool of mud.

Magic’s about understanding—and then manipulating—how viewers digest sensory information

In the last half decade, magic—normally deemed entertainment fit only for children and tourists in Las Vegas—has become shockingly respectable in the scientific world. Even I—not exactly renowned as a public speaker—have been invited to address conferences on neuroscience and perception. I asked a scientist friend (whose identity I must protect) why the sudden interest. He replied that those who fund science research find magicians “sexier than lab rats.”

I’m all for helping science. But after I share what I know, my neuroscientist friends thank me by showing me eye-tracking and MRI equipment, and promising that someday such machinery will help make me a better magician.

I have my doubts. Neuroscientists are novices at deception. Magicians have done controlled testing in human perception for thousands of years.

How Zara Grew Into the World’s Largest Fashion Retailer

Galicia, on the Atlantic coast of northern Spain, is the homeland of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, but is otherwise famous for being a place people try to leave. For much of the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of gallegos, as they are called, emigrated to countries as far away as Argentina to escape Galicia’s rural poverty. Today, however, even as Spain teeters on the edge of economic catastrophe, the Galician city La Coruña has attracted notice as the hometown of Amancio Ortega Gaona, the world’s third-richest man — he displaced Warren Buffett this year on the Bloomberg billionaire index — and the founder of a wildly successful fashion company, Inditex, more commonly known by its oldest and biggest brand, Zara.

William Black on Geithner & Obama

I wish people would stop asking me for insight into what Tim Geithner has been thinking since June 2009. I think I understand the President–you work 90 hours a week, 30 of which are ceremonial, 30 of which are coalition maintenance, and 30 of which are policy, of which macroeconomic and financial policy are only one of ten important issue areas. Thus if you are a president you spend three hours a week on macroeconomic and financial policy–about 30% of what we expect freshman taking “Principles of Economics” to spend. You can’t master any of the technical issues. You have to trust advisors.

But Geithner? The current theory is that he really did not understand and did not want to understand the difference between 1993 and 2009–that there is a big difference between a situation in which there is a threatened run from and one in which there is an active run to Treasuries, and a situation in which the clean-up of the financial mess is already well in hand and one in which it needs to be undertaken.

Inside the Secret World of Data Crunchers Who Helped Obama Win

In late spring, the backroom number crunchers who had powered Barack Obama’s campaign to victory noticed that George Clooney had an almost gravitational tug on West Coast females ages 40 to 49. The women were far and away the single demographic group most likely to hand over cash, for a chance to dine in Hollywood with Clooney — and Obama.

So as they did with all the other data collected, stored and analyzed in the two-year drive for re-election, Obama’s top campaign aides decided to put this insight to use. They sought out an East Coast celebrity who had similar appeal among the same demographic, aiming to replicate the millions of dollars produced by the Clooney contest. “We were blessed with an overflowing menu of options, but we chose Sarah Jessica Parker,” explains a senior campaign adviser. And so the next Dinner with Barack contest was born: a chance to eat at Parker’s West Village brownstone.

Is Corporate Media The New Funding Model For Serious Journalism?

As the business models for serious journalism continue to erode where will we get the quality media we need as a society to make important decisions about our future?

I’ve been warning people: “Special interest groups will gladly pay for the media they want you to read, but you won’t pay for the media you need to read.”

Software engineers have a saying: GIGO, garbage in, garbage out.

If you start with garbage data you will get a garbage result. That’s the future we are heading towards, a future where our media is corrupted with information that serves the goals of special interest groups.

Take a look at Australia where multi-billionaire mining magnate Gina Rinehart has been trying to acquire Fairfax Media, publisher of top newspapers, in a bid to counter anti-mining forces. We’ll see more of that as newspapers and other traditional media continue to weaken.

Behind the Iron Curtain Entry 4: Survival sometimes means collaboration. But it is no guarantee of success.

Wanda Telakowska did not begin her career as a Marxist. At different times an art teacher, designer, critic, and curator, Telakowska had in the 1930s been best known for her association with a Polish artistic group called ?ad, which conoisseurs of design history will recognize as a cousin of the British Arts and Crafts movement. ?ad sought to make use of traditional, folk, and peasant craftsmen, who still thrived in parts of southern and eastern Poland, and to use their work as the basis for a new and authentically “Polish” vernacular design. The artists and designers associated with ?ad believed that “contemporary” did not have to mean “modernist” or futuristic. Not everything had to be sleek or simplified in the machine age: folk designs for furniture, textiles, glass and ceramics could, they believed, be brought up-to-date, and even used as inspiration by industry.

By instinct and by training, Telakowska was no communist either. Many left-wing artists of the time, including the Bauhaus designers in Germany, spoke of sweeping away the past in the name of revolution, and starting from scratch. Telakowska, by contrast, retained a distinctly un-Communist, lifelong determination to find inspiration from the past. Nevertheless, after the war, she was determined to continue ?ad’s work, and toward that end she joined the new Communist government. She quickly found that her project—which favored “authentic” peasant art over the slicker modernism of urban intellectuals—overlapped with some of the aims of the Communist Party. As one cultural bureaucrat pointed out, folk art was more likely to appeal to the Polish laborer: “Our working class is closely connected to the countryside and feels more connected to the culture of folk art than to the culture of intellectual salons.”

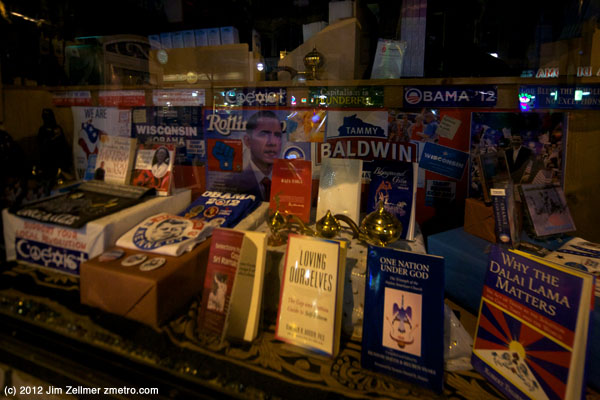

Madison Prepares for Monday’s Obama/Springsteen Campaign Event