Jay-Z’s new album and song lyrics show how our understanding of the Magna Carta has come a long way since barons imposed their will on King John in 1215

It was, as these things go, something of a flop. The Magna Carta was a document hammered out between King John and a group of feisty barons in the summer of 1215 that set out an agreement between them on the subjects of England’s taxation, feudal rights and justice.

It was the culmination of a sticky period for both parties, and must have been greeted with some eyebrow-raising on that evening’s edition of Newsnight. The most striking part of the charter allowed, for the first time, for the powers of the king to be limited by a written document. Observers hoped that it heralded a new era of collaboration between the monarch and his subjects.

But the dawn was false. The Magna Carta was valid for just 10 weeks.

The only reason the king had agreed to the terms of the charter was to play for time. He then appealed to Rome to declare the document null and void. By the end of the summer, a papal bull from Pope Innocent III granted him his wish. By the winter, England was embroiled in civil war. The following year John went on the offensive, celebrating a victory in the eastern counties with a feast of peaches and cider. They gave him dysentery. He died in October 1216.

Little of the drama and subterfuge of those politically febrile days can be detected in the small room of the British Library in which two of the four surviving copies of the first Magna Carta are kept. One of them is virtually illegible, having been damaged by fire in the 18th century. The other is a pretty tough read too, the text laid out austerely in a continuous flow of abbreviated Latin.

How a secretive panel uses data that distorts doctors’ pay

Peter Whoriskey and Dan Keating:

When Harinath Sheela was busiest at his gastroenterology clinic, it seemed he could bend the limits of time.

Twelve colonoscopies and four other procedures was a typical day for him, according to Florida records for 2012. If the American Medical Association’s assumptions about procedure times are correct, that much work would take about 26 hours. Sheela’s typical day was nine or 10.“I have experience,” the Yale-trained, Orlando-based doctor said. “I’m not that slow; I’m not fast. I’m thorough.”

This seemingly miraculous proficiency, which yields good pay for doctors who perform colonoscopies, reveals one of the fundamental flaws in the pricing of U.S. health care, a Washington Post investigation has found.

Unknown to most, a single committee of the AMA, the chief lobbying group for physicians, meets confidentially every year to come up with values for most of the services a doctor performs.

Those values are required under federal law to be based on the time and intensity of the procedures. The values, in turn, determine what Medicare and most private insurers pay doctors.

But the AMA’s estimates of the time involved in many procedures are exaggerated, sometimes by as much as 100 percent, according to an analysis of doctors’ time, as well as interviews and reviews of medical journals.

‘Irreplaceable Loss’: Luther Pamphlets Swiped from Museum

Church authorities and historians in Germany have reacted with shock to the news that three original printed pamphlets containing writings by Martin Luther were stolen from a museum in Eisenach, Germany, last week.

A member of staff at the Lutherhaus museum in Eisenach noticed that the 16th-century papers were missing from a glass case at 2 p.m. last Friday afternoon.

Even though the pamphlets are printed, they are unique because they contain hand-written notes by contemporaries of Luther.“Someone removed the fastening that kept the glass case shut. It wasn’t a very strong lock and it can’t be ruled out that this was a crime of opportunity,” the director of the museum, Jochen Birkenmeier, told SPIEGEL ONLINE.

From Tom Paine to Glenn Greenwald, we need partisan journalism

I would sooner engage you in a week-long debate over which taxonomical subdivision the duck-billed platypus belongs to then spend a moment arguing whether Glenn Greenwald is a journalist or not, or whether an activist can be a journalist, or whether a journalist can be an activist, or how suspicious we should be of partisans in the newsroom.

It’s not that those arguments aren’t worthy of time — just not mine. I’d rather judge a work of journalism directly than run the author’s mental drippings through a gas chromatograph to detect whether his molecules hang left or right or cling to the center. In other words, I care less about where a journalist is coming from than to where his journalism takes me.

Greenwald’s collaborations with source Edward Snowden, which resulted in Page One scoops in the Guardian about the National Security Agency, caused such a rip in the time-space-journalism continuum that the question soon went from whether Greenwald’s lefty style of journalism could be trusted to whether he belonged in a jail cell. Last month, New York Times business journalist Andrew Ross Sorkin called for the arrest of Greenwald (he later apologized) and Meet the Press host David Gregory asked with a straight face if he shouldn’t “be charged with a crime.” NBC’s Chuck Todd and the Washington Post‘s Walter Pincus and Paul Farhi also asked if Greenwald hadn’t shape-shifted himself to some non-journalistic precinct with his work.

We have good cause to abhor the surveillance state

Ah, German hypocrisy! During the cold war, you marched waving “Ami, Go Home” placards, but still let us protect you against the Soviets. Now you moan self-righteously about the National Security Agency and GCHQ reading your emails and listening to your mobile phone. You don’t acknowledge that – unlike the US or the UK – you have had no domestic terror attack in the past 10 years. That’s because we gave you information to prevent them; guess where we got it? Anyway, your Federal Intelligence Service snoops as much as it can. Except it can’t do that much. Whereas we – oh yes, we scan! Could it be that you’re jealous?

That about sums up the American and British response to the uproar about alleged US and UK spying activities in Germany revealed by the whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Sorry, friends: things are not that simple. This topic touches on historical sensitivities here. Our grandparents’ generation feared the early-morning knock of the Gestapo. During the cold war, West and East Germans alike were aware that their divided country was crawling with spooks of all denominations. We recognised that mutually assured espionage helped prop up the bipolar balance of power. (It also made for some superb spy thrillers.) Still, no one misses the sombre paranoia, reinforced in and after the 1970s by the ramping up of West Germany’s domestic intelligence services in response to homegrown terrorism.

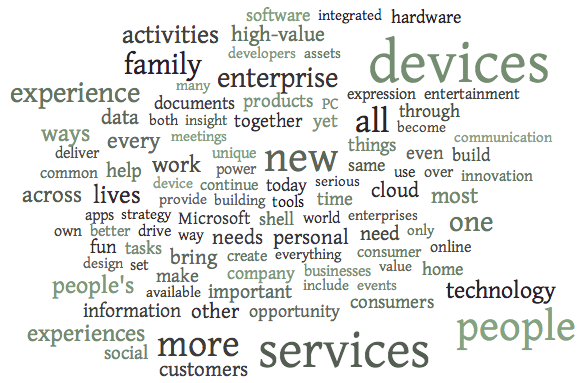

Microsoft Reorganization Memorandum Word Cloud

The Microsoft memorandum can be found here.

Ben Thompson: Why Microsoft’s Reorganization is a Bad Idea and Why Microsoft’s reorganization closes the books on an era of computing.

Snowden Backlash: US Media Get Personal

There’s another reason for the united media front: The Guardian is becoming a competitive threat for American media outlets. The first Snowden video interview received almost seven million clicks on the newspaper’s US website. “They set the US news agenda today,” Associated Press star reporter Matt Apuzzo tweeted enviously.

Why? Janine Gibson, the Guardian’s American chief, told the Huffington Post that their competition has a “lack of skepticism on a whole” when it comes to national security. Critical scrutiny, she said, has been considered “unpatriotic” since 9/11.

The greatest humiliation would be if the British usurper won a Pulitzer Prize. Only American media can apply for it, but the Prize committee accepted one submission by the Guardian last year. Its reasoning? The newspaper has an “unmistakable presence” in the United States.

Preferred Parking: Carpool M3

Journalism Is in a Disastrous State — But for a Handful of Millionaire Pundits, It’s a Wonderful Life

Mainstream journalism is, we’re often told, in a state of severe crisis. Newsroom employment began to decline as a result of corporate takeovers in the 1990s. Then the digital revolution destroyed the advertising market, plunging the industry into serious doubt about its very business model.

But times aren’t rough all around. There are many pundits and TV anchors who are doing very well in the media world, racking up millions of dollars from their media contracts, book deals and lucrative speaking fees. Though they don’t generally approach the compensation packages awarded to network morning show hosts like Matt Lauer or evening anchors like Diane Sawyer, they’re not exactly hurting.

Of course, being the boss means the biggest payday—and media company CEOs have been posting unbelievable incomes. In 2012, CBS head Les Moonves made $62 million, Disney’s Robert Iger made $37 million and Rupert Murdoch ofFox took home a comparatively modest $22 million ( New York Times,5/5/13). Don’t feel sorry for Murdoch, though; as No. 91 on Forbes’ list of the world’s richest people, with an estimated net worth of $11.2 billion, he’s unlikely to go to bed hungry.

“Living People Don’t Sell a Car Like This”