MICHAEL MUNGER, a professor of political science at Duke University, insightfully compares “tax expenditures” to the Catholic church’s practice of selling indulgences, which fomented the Reformation by sending Martin Luther into fit of righteous pique. Mr Munger reminds us that

Indulgences were “get out of purgatory free!” cards. Of course, it was the church that had created the idea of purgatory in the first place. Then the church granted itself the power to release souls from purgatory (for a significant fee, of course).As Luther put it, in his Thesis No. 27, “as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies out.”

If high tax rates are a sort of purgatory (and who doubts it?), then tax credits are indeed akin to indulgences. Mr Munger writes:

We let people out of tax purgatory if they own large houses, if they receive expensive health insurance from their employer, if they produce sugar or ethanol, or any of thousands of special categories. These categories have nothing to do with need (is there a national defense justification for a protected sugar industry?), but instead depend on how much these sinners are willing to pay to members of Congress.

“As the campaign contributions jingle into the campaign funds, the tax revenues fly out”, he adds. As a result, “we have categories within categories within subgroups, all at different prices, deductions or exemptions that release some elites from the published tax rates.

Category: Politics

The Scourge of the Faith-Based Paper Dollar: Jim Grant foresees a new American gold standard despite Wall Street’s stake in monetary chaos

Jim Grant’s father pursued a varied career, including studying the timpani. He even played for a while with the Pittsburgh Symphony. But the day came when he rethought his career choice. “For the Flying Dutchman overture,” says his son, “they had him cranking a wind machine.”

The younger Mr. Grant, who can be sardonic about his own chosen profession, might say he’s spent the past 28 years cranking a wind machine, though it would be a grossly unjust characterization. Mr. Grant is founder and writer of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, perhaps the most iconic of the Wall Street newsletters. He is also one of Wall Street’s strongest advocates of the gold standard, knowing full well it would take away much of Wall Street’s fun.

You might say that, as a journalist and historian of finance, he has been in training his whole life for times like ours—in which the monetary disorders he has so astutely chronicled are reaching a crescendo. The abiding interest of Grant’s, both man and newsletter, has been the question of value, and how to know it. “Kids today talk about beer goggles—an especially sympathetic state of perception with regard to a member of the opposite sex,” he says of our current market environment. “We collectively wear interest-rate goggles because we see market values through the prism of zero-percent funding costs. Everything is distorted.”

The Tragedy Of The Gas Tax

General Motors CEO Dan Akerson set off something of a firestorm a few weeks ago, when he said, in response to a question about forthcoming CAFE increases:

You know what I’d rather have them do — this will make my Republican friends puke — as gas is going to go down here now, we ought to just slap a 50-cent or a dollar tax on a gallon of gas.

Predictably, populists and economic alarmists of all stripes took great umbrage at Akerson’s candor, questioning his leadership of GM as well as his perspective on the shaky US economy. But Akerson is not alone in his support of some form of gas-tax increase. Bob Lutz and Tom Friedman (an odd couple right there, if ever there was one) agree with him. Edmunds CEO Jeremy Anwyl defended Akerson and even suggested a $2/gallon tax earlier this year. Bill Ford and AutoNation’s Mike Jackson are of the same mind as now-retired Republican Senator George Voinovich on the issue. And yet, inside the Beltway, the subject tends to draw a chuckle and a roll of the eyes. Everyone wants it, but nobody wants it.

Iraq 2011: Jet skiing the Triangle of Death, listening to Bee Gee songs–and pondering what comes next

The taxi driver to Beirut airport tells me that yom al-qiyama (the day of judgment) is approaching. There will be a big explosion soon — a very big explosion. The revolutions sweeping the Arab World are not good. Islamic parties will come to power everywhere. There will be no more Christians left in the Middle East. Believe me, believe me, he insists. In anticipation, he will make the Hajj to Mecca this year, inshallah. I tell him that I am traveling to Iraq as a tourist. The look he gives me in the rear view mirror says it all: He thinks I am crazy.

I am heading back to Iraq nine months after I left my job as Political Advisor to the Commanding General of U.S. Forces Iraq. Earlier this year, a Sheikh emailed me from his iPad, “Miss Emma we miss you. You must come visit us as a guest. You will stay with me. And you will have no power!” I am excited and nervous. The plane is about a third full. I am the only foreigner. I look around at my fellow passengers. I wonder who they are and whether they bear a grudge for something we might have done.

The flight is one and a half hours long. I read and doze. As we approach Iraq, I look out of the window. The sky is full of sand and visibility is poor. But I can make out the Euphrates below. Land of the two rivers, I am coming back.

I do not have an Iraqi visa. Visas issued in Iraqi Embassies abroad are not recognized by Baghdad airport. I have a letter from an Iraqi General in the Ministry of Interior, complete with a signature and stamp. In the airport, I present my passport and letter, fill out a form, pay $80, and receive a visa within 15 minutes. I collect my bag. I am through. I want to reach down and touch the ground, this land that has soaked up so much blood over the years — ours and theirs.

US doctors braced for deep cuts in spending

Doctors treating the poor in the US are braced for significant reductions to their services amid increased pressure from both the Obama administration and Republicans for deep cuts in health spending.

Twenty-nine Republican governors have called for greater flexibility in how states administer Medicaid programmes for the poor, a move which coincides with the Obama administration’s withdrawal of stimulus funds used to pay for treatment.

Nearly 49m people in the US, or one in six Americans, were covered by Medicaid in 2009. The figure is thought to be higher today.

The federal government increased its subsidies to the states under the stimulus programme, spending $2.68 for every dollar a state spent on Medicaid, nearly twice as much as before the stimulus.

Madison Farmer’s Market Scenes June 3, 2011

The Dilemma

If there is one most frightening thing that war always exposes, even if one is on the winning side, it’s weakness in the supply logistics. While most never consider it, official policy often changes during a war because supplies that are critical to the war effort seem in danger of being disrupted. Such jeopardy, moreover, forces the accountants, economists and politicians waging the conflict to start thinking about how the world will be changed once the fighting has ended.

Few today appreciate the fact that our foreign policy, particularly as it is tied to the Middle East, came about because of just such concerns in the first years of the Second World War. As one might expect, that official policy was based on real fears that America would one day run out of oil.

“The European War”

It was the summer of 1941 and the State Department had requested that the White House include Saudi Arabia in our Lend Lease program. It wasn’t because the Saudis were going to become a direct ally against the European Axis Powers, but because we were about to embargo U.S. oil shipments to Japan. Many believed – correctly, as it turned out – that this would probably lead to hostilities with Japan that would draw us into the war.

Standard Oil of California, which had been drilling for oil in Bahrain for over a decade, now had oil concessions granted by King ibn Saudi. The first six wells Standard drilled into the Arabian desert were nothing to write home about, but when Well No. 7 came in on March 4, 1938, the engineers and wildcatters all knew that Saudi Arabia was going to be an oil bonanza.

Yet on July 18, 1941, Roosevelt refused the request for Lend Lease for Saudi Arabia. He saw no immediate benefit to diverting U.S. dollars overseas simply because Standard had oil concessions there. In any case, the outbreak of the European War in 1939 had reduced oil production in the Kingdom to an insignificant volume — a trickle, considering that American oil amounted to 60 percent of the world’s crude at the time. Instead Roosevelt asked Federal Loan Administrator Jesse Jones to look into the possibility of having England deal with the Saudi King’s pressing needs.

Stupid IT Tricks: Medical Records, or Why a Federal Subsidy Makes No Sense (I Agree)

A reader asked me to write tonight about the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, which is about as far from something I would like to write about as I can imagine, but this is a full service blog so what the heck. The idea behind the law is laudable — standardized and accessible electronic health records to allow any doctor to know what they need to know in order to treat you. There’s even money to pay for it — $30 billion from the 2009 economic stimulus that you’d think would have been spent back in 2009, right? Silly us. Now here’s the problem: we’re going to go through that $30 billion and end up with nothing useful. There has to be a better way. And I’m going to tell you what it is.

But first a word from my reader:

Henry Kissinger talks to Simon Schama

Not so much, though, as to get in the way of treating China as an indispensable element in any stabilisation of perilous situations in Korea and Afghanistan. Without China’s active participation, any attempts to immunise Afghanistan against terrorism would be futile. This may be a tall order, since the Russians and the Chinese are getting a “free ride” on US engagement, which contains the jihadism which in central Asia and Xinjiang threatens their own security. So was it, in retrospect, a good idea for Barack Obama to have announced that this coming July will see the beginning of a military drawdown? The question triggers a Vietnam flashback. “I know from personal experience that once you start a drawdown, the road from there is inexorable. I never found an answer when Le Duc Tho was taunting me in the negotiations that if you could not handle Vietnam with half-a-million people, what makes you think you can end it with progressively fewer? We found ourselves in a position where to maintain … a free choice for the population in South Vietnam … we had to keep withdrawing troops, thereby reducing the incentive for the very negotiations in which I was engaged. We will find the same challenge in Afghanistan. I wrote a memorandum to Nixon which said that in the beginning of the withdrawal it will be like salted peanuts; the more you eat, the more you want.”

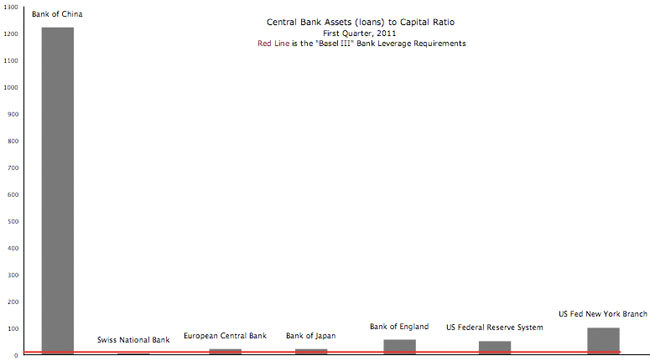

Investing, Risk, Politics & Taxes: Global Central Bank Leverage

Source: Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, 5/20/2011 edition. Worth considering for financial & risk planning.

Related: Britannica: Central Banks and currency.

Basell III details: Clusty.com and Blekko.