By the time this column is published I will be on holiday in France, and the US might finally have stepped back from the abyss of debt default.

Viewed from Europe, the American financial uproar is baffling. It is not just the entirely avoidable nature of the crisis. It is also its timing. The entire European political calendar is constructed around the idea that nothing ever happens – or should be allowed to happen – in August.

The drama that surrounded the emergency eurozone summit in Brussels in late July was partly caused by the threat of financial chaos, if Greece was not lent more money. But an unstated reason for the sense of urgency of the leaders around the conference table was a desperate desire to get a deal wrapped up – before the holiday season began in earnest.

Judged in these limited terms, the summit deal might be counted a success. It surely has not solved the crisis in the eurozone. But the European Union’s leaders might have done enough to ensure that there will probably be no call for further emergency summits until after the rentrée in early September.

Category: Investing

Fiscal Indulgences

MICHAEL MUNGER, a professor of political science at Duke University, insightfully compares “tax expenditures” to the Catholic church’s practice of selling indulgences, which fomented the Reformation by sending Martin Luther into fit of righteous pique. Mr Munger reminds us that

Indulgences were “get out of purgatory free!” cards. Of course, it was the church that had created the idea of purgatory in the first place. Then the church granted itself the power to release souls from purgatory (for a significant fee, of course).As Luther put it, in his Thesis No. 27, “as the penny jingles into the money-box, the soul flies out.”

If high tax rates are a sort of purgatory (and who doubts it?), then tax credits are indeed akin to indulgences. Mr Munger writes:

We let people out of tax purgatory if they own large houses, if they receive expensive health insurance from their employer, if they produce sugar or ethanol, or any of thousands of special categories. These categories have nothing to do with need (is there a national defense justification for a protected sugar industry?), but instead depend on how much these sinners are willing to pay to members of Congress.

“As the campaign contributions jingle into the campaign funds, the tax revenues fly out”, he adds. As a result, “we have categories within categories within subgroups, all at different prices, deductions or exemptions that release some elites from the published tax rates.

The Scourge of the Faith-Based Paper Dollar: Jim Grant foresees a new American gold standard despite Wall Street’s stake in monetary chaos

Jim Grant’s father pursued a varied career, including studying the timpani. He even played for a while with the Pittsburgh Symphony. But the day came when he rethought his career choice. “For the Flying Dutchman overture,” says his son, “they had him cranking a wind machine.”

The younger Mr. Grant, who can be sardonic about his own chosen profession, might say he’s spent the past 28 years cranking a wind machine, though it would be a grossly unjust characterization. Mr. Grant is founder and writer of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, perhaps the most iconic of the Wall Street newsletters. He is also one of Wall Street’s strongest advocates of the gold standard, knowing full well it would take away much of Wall Street’s fun.

You might say that, as a journalist and historian of finance, he has been in training his whole life for times like ours—in which the monetary disorders he has so astutely chronicled are reaching a crescendo. The abiding interest of Grant’s, both man and newsletter, has been the question of value, and how to know it. “Kids today talk about beer goggles—an especially sympathetic state of perception with regard to a member of the opposite sex,” he says of our current market environment. “We collectively wear interest-rate goggles because we see market values through the prism of zero-percent funding costs. Everything is distorted.”

America’s Hottest Investment: Farmland

This is usually a slow time of the year for farm sales. It’s past prime planting season. Yet, Sam Kain, Des Moines area manager for land sales at Farmers National, is busy. He has 3 auctions this week. Most of the 30 or so bidders who show up will be farmers. But an increasing number of people buying land these days have no intention of planting seeds, at least not themselves. They are investors and a growing number of them are getting interested in farmland.

Just how hot is American farmland? By some accounts the value of farmland is up 20% this year alone. That’s better than stocks or gold. During the past two decades, owning farmland would have produced an annual return of nearly 11%, according to Hancock Agricultural Investment Group. And that covers a time period when tech stocks boomed and crashed, and housing boomed and crashed. So at a time when investors are still looking for safety, farmland is becoming the “it” investment.

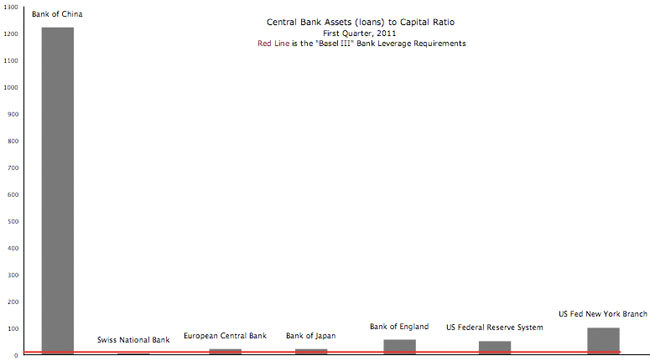

Investing, Risk, Politics & Taxes: Global Central Bank Leverage

Source: Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, 5/20/2011 edition. Worth considering for financial & risk planning.

Related: Britannica: Central Banks and currency.

Basell III details: Clusty.com and Blekko.

Former Fed Vice Chair: Kohn ‘regrets’ pain of millions in financial crisis

The former vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve has said he “deeply regretted” the pain caused to millions of people around the world from the financial crisis, admitting that “the cops weren’t on the beat”.

Don Kohn’s apology for the actions of Federal Reserve in the run-up to the financial and economic crisis goes significantly further than the limited responsibility taken by his former boss, Alan Greenspan.

Speaking to British MPs at a confirmation hearing on Tuesday, Mr Kohn nevertheless said his experience would be valuable for the Bank of England, where he has been appointed to a new committee with powers to guide UK financial stability.

“I believe I will not make the same mistake twice,” he said.

Mr Kohn has been appointed to the Bank’s new Financial Policy Committee, which will soon have powers to change system-wide UK financial regulations and even limit borrowing by households and companies if it thinks there are threats to financial stability.

Having been a strong advocate of the Greenspan doctrine not to burst asset bubbles but to mop up any mess after a crash, Mr Kohn recanted much of his previous view in front of MPs. He said he had “learnt quite a few lessons – unfortunately” from the financial crisis, including that people in markets can get excessively relaxed about risk, that risks are not distributed evenly throughout the financial system, that incentives matter even more than he thought and transparency is more important than he thought.

The People vs. Goldman Sachs

A Senate committee has laid out the evidence. Now the Justice Department should bring criminal charges.

They weren’t murderers or anything; they had merely stolen more money than most people can rationally conceive of, from their own customers, in a few blinks of an eye. But then they went one step further. They came to Washington, took an oath before Congress, and lied about it.

Thanks to an extraordinary investigative effort by a Senate subcommittee that unilaterally decided to take up the burden the criminal justice system has repeatedly refused to shoulder, we now know exactly what Goldman Sachs executives like Lloyd Blankfein and Daniel Sparks lied about. We know exactly how they and other top Goldman executives, including David Viniar and Thomas Montag, defrauded their clients. America has been waiting for a case to bring against Wall Street. Here it is, and the evidence has been gift-wrapped and left at the doorstep of federal prosecutors, evidence that doesn’t leave much doubt: Goldman Sachs should stand trial.

This article appears in the May 26, 2011 issue of Rolling Stone. The issue is available now on newsstands and will appear in the online archive May 13.

The great and powerful Oz of Wall Street was not the only target of Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: Anatomy of a Financial Collapse, the 650-page report just released by the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by Democrat Carl Levin of Michigan, alongside Republican Tom Coburn of Oklahoma. Their unusually scathing bipartisan report also includes case studies of Washington Mutual and Deutsche Bank, providing a panoramic portrait of a bubble era that produced the most destructive crime spree in our history — “a million fraud cases a year” is how one former regulator puts it. But the mountain of evidence collected against Goldman by Levin’s small, 15-desk office of investigators — details of gross, baldfaced fraud delivered up in such quantities as to almost serve as a kind of sarcastic challenge to the curiously impassive Justice Department — stands as the most important symbol of Wall Street’s aristocratic impunity and prosecutorial immunity produced since the crash of 2008.

Seven tricky questions for Mr Buffett

Until this week, only one topic was off-limits for questions to Warren Buffett at Saturday’s annual gathering of Berkshire Hathaway shareholders in Omaha: how serious is the Dave Sokol affair?

On Wednesday, however, the company issued an 18-page report from its audit committee about the former star executive’s trading in shares in Lubrizol, a chemicals group later bought by Berkshire, and declared open season for all questions to Mr Buffett.

Here are my seven:

1. How serious is the Dave Sokol affair?

You are the world’s most famous long-term investor. Recently, Berkshire’s shares have lagged behind the S&P 500, but your record of outperformance over more than four decades speaks for itself. Even big, conservative bets, such as the 2009 investment in Burlington Northern Santa Fe railway, have been well timed. But Mr Sokol was a frontrunner to succeed you as chief executive. You lauded him regularly in your annual letter to shareholders. His abrupt resignation and the circumstances surrounding it seem to suggest that this is more than just a blip.

2. Do you love some of your managers too much?

Oil: We’re Being Had Again

No matter how many of his Fed presidents claim they are not to blame for the high price of oil, the real problem starts with Ben Bernanke. The fact is that when you flood the market with far too much liquidity and at virtually no interest, funny things happen in commodities and equities. It was true in the 1920s, it was true in the last decade, and it’s still true today.

Richard Fisher, president of the Dallas Federal Reserve, spoke in Germany in late March. Reuters quoted him as saying, “We are seeing speculative activity that may be exacerbating price rises in commodities such as oil.” He added that he was seeing the signs of the same speculative trading that fueled the first financial meltdown reappearing.

Here Fisher is in good company. Kansas City Fed President Thomas Hoening, who has been a vocal critic of the current Fed policy of zero interest and high liquidity, has suggested that markets don’t function correctly under those circumstances. And David Stockman, Ronald Reagan’s Budget Director, recently wrote a scathing article for MarketWatch, titled “Federal Reserve’s Path of Destruction,” in which he criticizes current Fed policy even more pointedly. Stockman wrote, “This destruction is, namely, the exploitation of middle class savers; the current severe food and energy squeeze on lower income households … and the next round of bursting bubbles building up among the risk asset classes.”

The 30-Cent Tax Premium: Tax compliance employs more workers than Wal-Mart, UPS, McDonald’s, IBM and Citigroup combined.

There is a lot more to taxes than simply paying the bill. Taxpayers must spend significantly more than $1 in order to provide $1 of income-tax revenue to the federal government.

To start with, individuals and businesses must pay the government the $1 in revenue plus the costs of their own time spent filing and complying with the tax code; plus the tax collection costs of the IRS; plus the tax compliance outlays that individuals and businesses pay to help them file their taxes.

In a study published last week by the Laffer Center, my colleagues Wayne Winegarden, John Childs and I estimate that these costs alone are a staggering $431 billion annually. This is a cost markup of 30 cents on every dollar paid in taxes. And this is not even a complete accounting of the costs of tax complexity.

Like taxes themselves, tax-compliance costs change people’s behavior. Taxpayers, whether individuals or businesses, respond to taxes and tax-compliance costs by changing the composition of their income, the location of their income, the timing of their income, and the volume of their income. So long as the cost of changing one’s income is lower than the taxes saved, the taxpayer will engage in these types of tax-avoidance activities.