Category: History

The Fed’s moral hazard maximising strategy

The reports on the evidence given by the Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Don Kohn, to the Senate Banking Committee about the Fed’s role in the government’s rescue of AIG, have left me speechless and weak with rage. AIG wrote CDS, that is, it sold credit default swaps that provided the buyer of the CDS (including some of the world’s largest banks) with insurance against default on bonds and other credit instruments they held. Of course the insurance was only as good as the creditworthiness of the party writing the CDS. When it was uncovered during the late summer of 2008, that AIG had nurtured a little rogue, unregulated investment banking unit in its bosom, and that the level of the credit risk it had insured was well beyond its means, the AIG counterparties, that is, the buyers of the CDS, were caught with their pants down.

Instead of saying, “how sad, too bad” to these counterparties, the Fed decided (in the words of the Wall Street Journal), to unwind “.. some AIG contracts that were weighing down the insurance giant by paying off the trading partners at the full value they expected to realize in the long term, even though short-term values had tumbled.”

An LSE colleague has shown me an earlier report in the Wall Street Journal (in December 2008), citing a confidential document and people familiar with the matter, which estimated that about $19 billion of the payouts went to two dozen counterparties between the government bailout of AIG in mid-September and early November 2008. According to this Wall Street Journal report, nearly three-quarters was reported to have gone to a group of banks, including Société Générale SA ($4.8 billion), Goldman Sachs Group ($2.9 billion), Deutsche Bank AG ($2.9 billion), Credit Agricole SA’s Calyon investment-banking unit ($1.8 billion), and Merrill Lynch & Co. ($1.3 billion). With the US government (Fed, FDIC and Treasury) now at risk for about $160 bn in AIG, a mere $19 bn may seem like small beer. But it is outrageous. It is unfair, deeply distortionary and unnecessary for the maintenance of financial stability.

Don Kohn ackowledged that the aid contributed to “moral hazard” – incentives for future reckless lending by AIG’s counterparties – it “will reduce their incentive to be careful in the future.” But, here as in all instances were the weak-kneed guardians of the common wealth (or what’s left of it) cave in to the special pleadings of the captains of finance, this bail-out of the undeserving was painted as the unavoidable price of maintaining, defending or restoring financial stability. What would have happened if the Fed had decided to leave the AIG counterparties with their near-worthless CDS protection?

The organised lobbying bulldozer of Wall Street sweeps the floor with the US tax payer anytime. The modalities of the bailout by the Fed of the AIG counterparties is a textbook example of the logic of collective action at work. It is scandalous: unfair, inefficient, expensive and unnecessary.

Wall Street on the Tundra

celand’s de facto bankruptcy—its currency (the krona) is kaput, its debt is 850 percent of G.D.P., its people are hoarding food and cash and blowing up their new Range Rovers for the insurance—resulted from a stunning collective madness. What led a tiny fishing nation, population 300,000, to decide, around 2003, to re-invent itself as a global financial power? In Reykjavík, where men are men, and the women seem to have completely given up on them, the author follows the peculiarly Icelandic logic behind the meltdown.

by MICHAEL LEWIS April 2009

Just after October 6, 2008, when Iceland effectively went bust, I spoke to a man at the International Monetary Fund who had been flown in to Reykjavík to determine if money might responsibly be lent to such a spectacularly bankrupt nation. He’d never been to Iceland, knew nothing about the place, and said he needed a map to find it. He has spent his life dealing with famously distressed countries, usually in Africa, perpetually in one kind of financial trouble or another. Iceland was entirely new to his experience: a nation of extremely well-to-do (No. 1 in the United Nations’ 2008 Human Development Index), well-educated, historically rational human beings who had organized themselves to commit one of the single greatest acts of madness in financial history. “You have to understand,” he told me, “Iceland is no longer a country. It is a hedge fund.”

Uwe Reinhardt on the health of the economy and the economics of health

My friend professor Uwe E. Reinhardt of Princeton University presented ECONOMIC TRENDS IN U.S HEALTH CARE: Implications for Investors, at J.P. Morgan’s annual healthcare conference on Tuesday, January 13 2009. The first half of the presentation (46 slides!) deals with macroeconomic and financial issues in Uwe’s inimitable style – equal portions of wit and insight. The second half deals with the embarrassing mess known as health care in the US.

VR Scene: The Statue of Liberty on Madison’s Lake Mendota

The Statue of Liberty reappeared on Lake Mendota recently, celebrating the 30th anniversary of its first visit. Visit via this full screen vr scene. More about the first visit, sponsored by the “Pail & Shovel Party”.

For Some Taxi Drivers, a Different Kind of Traffic

The tour guide’s voice dropped to a whisper as he pointed out the left side of his open-air taxi and said conspiratorially: “See that house? It belongs to Chapo.”

At the spot, where Mr. Félix’s brother Ramo?n was killed in 2002, in an infamous murder.

The State Department warns tourists about the drug wars.

The guide recovered his normal tone around the corner, well out of earshot of anyone who might be inside what he claimed was one of the beachfront hideaways of Mexico’s most wanted drug trafficker, Joaquín Guzmán Loera, who is known universally by the nickname El Chapo, or Shorty.

Although Mazatlán markets itself as a seaside paradise in which the roughest things one might encounter are ocean swells, it is a beach resort with a dark side — one that many enterprising taxi drivers are exploiting with unauthorized “narco-tours.”

Mexicans are fed up with their country’s unprecedented level of bloodshed as rival drug cartels clash with the authorities and among themselves. But the outrage is tinged by a fascination with the colorful lives of the outlaws.

I visited Mazatlan many years ago, during college.

Visualization of the Credit Crisis

Chuck Taylor

Charles Hollis “Chuck” Taylor looked down at his shoes and saw opportunity.

His Spaulding basketball sneakers were killing his feet.

Tired of the pain, the player hobbled into Converse Rubber Co. in 1921 and told owner Marquis Converse what he wanted — a sneaker with a higher ankle and a patch for better support, and a rubber sole with treads that made for a better grip for faster running and breaks.

Converse agreed to cobble one together. The upgraded All-Star shoe was born.

Over the next half-century, Taylor almost single-handedly established the Converse All-Star as the most popular athletic shoe ever.

Known as Chucks in tribute to Taylor, the shoes sold 750 million pairs before Converse was bought by Nike in 2003.

Taylor didn’t just build a brand. He also changed the face of basketball through integration, boosted the careers of some of the game’s most legendary coaches and helped make roundball one of the most popular sports in the world, notes Abraham Aamidor, author of “Chuck Taylor: Converse All Star.”

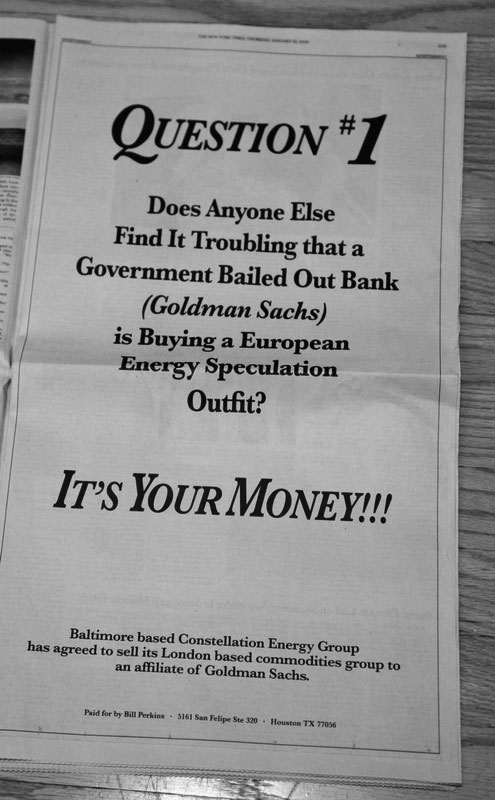

Our Tax Dollars Supporting Goldman Sach’s Latest Acquisition

Bill Perkins is at it again in the New York Times. More Bill Perkins activism on the bailout/splurge, here.