Alexandra Suich Bass [Twitter] and the Economist consider America’s future via the political, economic, social, environmental and cultural climates of America’s two largest states.

The articles:

1. America’s future will be written in the two mega-states:

IN THE CABLE-NEWS version of America, the president sits in the White House issuing commands that transform the nation. Life is not like that. In the real version of America many of the biggest political choices are made not in Washington but by the states—and by two of them in particular.

Texas and California are the biggest, brashest, most important states in the union, each equally convinced that it is the future (see our Special report in this issue). For the past few decades they have been heading in opposite directions, creating an experiment that reveals whether America works better as a low-tax, low-regulation place in which government makes little provision for its citizens (Texas), or as a high-tax, highly regulated one in which it is the government’s role to tackle problems, such as climate change, that might ordinarily be considered the job of the federal government (California). Given the long-running political dysfunction in Washington, the results will determine what sort of country America becomes almost as much as the victor of the next presidential election will.

That is partly a function of size. One in five Americans calls Texas or California home. By 2050 one in four will. Over the past 20 years the two states have created a third of new jobs in America. Their economic heft rivals whole countries’. Were they nations, Texas would be the tenth-largest, ahead of Canada by GDP. California would be fifth, right behind Germany.

Texas and California are also already living America’s demographic future. Hispanics are around 40% of the two states’ populations, double the national average. Both states were early to become majority-minority. In California non-whites have outnumbered whites since 2000, and in Texas since 2005. The rest of the country is not expected to reach this threshold until the middle of the century. California and Texas educate nearly a quarter of American children, many of them poor and non-native English-speakers. Their proximity to Mexico, a country that both used to be a part of, means that as Washington procrastinates on updating America’s immigration laws they must live with the consequences.

2. California and Texas have different visions for America’s future:

n texas an unexpected enemy gets a lot of attention. In a television ad for lieutenant-governor that aired last year, Dan Patrick, the winning Republican candidate, looked sternly at the camera and warned of a grave danger. “Truth is, Democrats want to turn Texas into California,” he said. “Well, I’m not about to let that happen. What about you?” United in concern is Greg Abbott, Texas’s Republican governor. He predicts that excessive regulation could turn “the Texas dream into a California nightmare”. “Don’t California my Texas” has become a rallying cry for Republicans in the Lone Star State. You can even buy the bumper-sticker.

Some competitive jousting between the two is inevitable. California, with 40m inhabitants, and Texas, with 29m, are the states with the largest populations, with more than one-fifth of Americans claiming them as home. They also have the biggest economies. If they were countries, they would be the fifth- and tenth-largest in the world (see chart), with around $3trn and $1.8trn in gdp, respectively.

3. Many people are moving from California to Texas:

Between 2007 and 2016 a net 1m American residents, or 2.5% of the state’s population, left California for another state. Texas was the most popular destination, attracting more than a quarter of them. More Americans have left California than moved there every year since 1990, though immigrants still arrive from abroad.

Companies are also moving. Last year McKesson, a medical-supplies company, and Core-Mark, a supplier to convenience stores, shifted their headquarters from California to Texas, as did Jamba Juice, a smoothie company. Many Californian firms are also adding jobs outside the Golden State. Charles Schwab, a financial-brokerage firm based in San Francisco, received more than $6m in incentives from Texas, and by the end of this year will have more employees there than in California.

What explains the one-way traffic? There are four reasons for California’s weaker position. First, it has become very expensive, especially for housing. “If there’s one risk factor in this state, it’s affordability,” says Gavin Newsom, California’s governor. “The thing we most pride ourselves on—the California dream, a notion of social mobility that we export around the world—is in peril.” A third of Californians are thinking of moving out of state because of the high cost of housing, according to a recent survey by the Public Policy Institute of California, a non-profit research firm. Most of those leaving California for Texas earn less than $50,000 a year and have only a high-school education (see chart).

4. Public education in both California and Texas is poor:

THEIR TASK is to educate whole generations, but if California and Texas were to be graded for their achievements in the classroom, they would barely pass. They rank 36th and 41st, respectively, out of 51 states (including Washington, DC) for educational outcomes, according to Education Week, a news firm. Only 29% of fourth-graders (aged 9-10) in Texas and 31% of their counterparts in California are proficient in reading at their grade level, compared with 35% nationally, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which measures student achievement (see charts on next page).

Since nearly a quarter of America’s public-school students are educated in California and Texas, the states’ performance matters profoundly for the country’s future. Yet less than 7% of economically disadvantaged kids are prepared for college, compared with 27% of children who are not economically disadvantaged. Those who enroll in community college or university in either state can spend months taking remedial courses before their coursework counts towards a degree, says Jim Lanich of Educational Results Partnership, an NGO. California’s students underperform Texas’s in several areas, including maths and science, and its Hispanic and African-American students do worse, too. But neither state has much to boast about.

Education is the biggest budget item in both states, costing $100bn per year in California and $50bn in Texas. But disenchantment is growing. “Education is the single largest enterprise in California. It has 6m student customers. And it sucks,” exclaims David Crane of Govern for California, a political outfit. A high-ranking education official in Texas compares his state’s poor performance to “being the thinnest fat dude. It’s not adequate for our kids.” Why, then, is performance so disappointing?

Both states have a difficult assignment. Around three-fifths of their students are economically disadvantaged and one-fifth are bilingual or still learning English, making their task especially challenging. But other factors are also at play. One is investment. In the fiscal year 2015-16 California spent $11,420 per pupil, 22% more than Texas but 4% less than the national average, according to the National Centre for Education Statistics, which tracks spending. Funding for education in California has risen by 60% since 2010 and is at a 30-year high, but given the needs and backgrounds of its students the state still underinvests.

California’s high costs help explain why increased spending has not produced better results. The average teacher’s salary in California is around $79,000, which is 50% more than in Texas, but that does not stretch far because of the extortionate cost of living. Many teachers struggle to buy their own house, says Eric Heins, who runs the California Teachers Association, a union.

5. California and Texas are both failing their neediest citizens:

TEXAN LEADERS are proudly thrifty. They also believe that cowboy boots are a legitimate fashion choice and that bootstraps are tools by which people should pull themselves up. Visitors to the website of the department overseeing welfare are encouraged to share their ideas for cost savings. Texas’s constitution, unusually, specifies a spending cap on aid for poor families and children (at 1% of the annual budget). “It seems like California measures success by the number of people who are dependent on government programmes,” quips Greg Abbott, the governor. “We define success by the number of people who are employed.”

California’s official poverty rate is 13% and Texas’s is 14%, putting them in the middle of the national range. However, after factoring in the cost of living, the Lone Star State’s poverty rate is nearly 15%, the tenth-highest. The Golden State, at 19%, has the highest. The huge gaps between the wealth of the top 5% and bottom 20% make California the second most unequal state after New York, with Texas in tenth place, according to the Centre for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), a think-tank.

California’s poverty rate is high despite heavy investment to counter it. It has 38% more people, but its spending on public welfare is 120% higher than Texas’s. However, the cost of living in California is 40% higher than the national average, whereas in Texas it is around 9% below the average. Housing is the primary culprit, responsible for around 80% of the higher cost of living in California. Around one in three Californian renters spends at least half their income on rent. “In California it’s harder to make it on your own, but there are supports,” explains Heather Hahn of the Urban Institute, a think-tank. “In Texas you may be better able to make it on your own because it is cheaper to live, but if you can’t, there’s less of a safety-net there for you.”

Both states accept federal funds for social-welfare programmes, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme, which provides food stamps to the needy. “Texas is pragmatic,” explains Ken Miller of Claremont McKenna College. “It’s willing to accept a dollar if the federal government wants to give it a dollar, but it isn’t willing to follow a government mandate.” California goes further, supplementing many federal programmes with money of its own, whereas Texas mostly does not.

6. California is a leader on environmentalism:

VISITORS TO THE Capitol in Sacramento, the seat of California’s state government, confront an 800lb grizzly bear outside the governor’s office. The bulky bronze statue of the official state animal showcases California’s environmental focus, which sadly developed only after the last remaining grizzly was shot nearly a century ago. The state’s environmentalism has produced many benefits. Its high standards for energy efficiency, for example, have helped to bring more fuel-efficient cars and fewer carbon-intensive products to the rest of the country.

In 2006 California established the first comprehensive greenhouse-gas regulatory programme in America and has adopted more zealous targets to reduce emissions than many signatories to the Paris Agreement, from which America withdrew. “We have stepped in on climate change where the federal government has stepped away,” says the governor, Gavin Newsom. California’s leadership on the environment has won it kudos, but it has also exacerbated the housing shortage and high cost of living.

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which requires state and local agencies to review the environmental impact of new projects, is one example. Signed into law in 1970 by the then governor, Ronald Reagan, CEQA initially applied to public-works projects, but later expanded to housing. Today those opposed to new development can bring CEQA lawsuits, holding up projects for years and adding to developers’ costs, which are subsequently passed on to consumers. Even a top adviser to Mr Newsom says that CEQA “is the standard-bearer for what’s wrong with California”.

Some of the state’s other standards for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions contribute to higher housing costs. Many new homes are required to install solar panels, and construction is encouraged near transit hubs, where units are more expensive than less-dense housing farther away from job centres.

7. Immigration shapes the politics of California and Texas:

SEVERAL THOUSAND feet up in the air, under the deafening whirr of the rotor blades of a helicopter belonging to Texas’s department of public safety, your correspondent found it easy to lose track of which country she was flying over. Much of the border between Texas and Mexico is the Rio Grande river, and the land on both sides looks similar. There is, however, one unmistakable clue: the direction of those crossing the river. Even in broad daylight, small groups of people are wading, swimming and rafting across. It is a one-way flow of human traffic.

The different philosophies of California and Texas, which were both once part of Mexico, can be summed up by what they do on their southern border. California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, recently withdrew several hundred National Guard troops from southern California in a symbolic protest at President Donald Trump’s hardline stance on immigration. Texas, by contrast, spends $400m a year of its own money to police the border. This investment has been essential in reducing crime in the Rio Grande Valley, says Steven McCraw, who is in charge of the department of public safety.

For much of the past century immigration has spurred economic prosperity in the country as a whole, and in California and Texas in particular. Around five in ten workers in Texas were not born there. Half of those came from another American state, and half from overseas. Texas and California have the largest share of undocumented immigrants in the country, an estimated 3.8m, or 36% of those nationwide.

Back where they came from

According to the Pew Research Centre, a think-tank, in 2016 undocumented immigrants accounted for 6% of the two states’ total population and 8.5% of their workforce, filling vital jobs in industries like agriculture and construction. The number of people coming across the border has declined from a peak of around two decades ago, but recently there has been an uptick. In May more than 144,000 people were apprehended in the south-west border region, the most since 2007.

8. Texas seems better placed to adapt than California:

“THERE’S A TEXAN expression, ‘You dance with the one who brung ya’,” says Tom Luce, with a serious face and a strong drawl. “But oftentimes you can’t just dance with who brought you. You’ve got to face the future.” Mr Luce founded a law firm, Hughes & Luce, and served under several Texan governors and as assistant secretary of education when George W. Bush was president. He has been a beneficiary of and advocate for Texas’s rise, but thinks that the state faces long-term challenges that political leaders are ignoring, such as a dwindling supply of skilled workers and ever rising health-care costs.

Mr Luce is the founder of Texas 2036, a group that collects data to reveal Texas’s relative position and catalyse a strategic plan for the state. “It’s akin to, if you were running IBM 30 years ago, you’d ask, what’s the competitive landscape out there and what are the dangers?” says Mr Luce, who thinks Texas should “invest incrementally, solving problems 5% a year for 20 years”.

A similar report, called Texas 2000, was commissioned in 1982 under a previous governor, Bill Clements. It guided the state’s investments in water and roads. Mr Luce is the most prominent example of a growing group of forward-thinking Texans who are quietly concerned about whether the Lone Star State will be able to maintain its edge. “The challenge for Texas is and has been, are we willing to match our grand words with bold action?” says Mr Smith. “I could go down the list of social and physical infrastructure investments not being made.”

California, too, has its critics, who believe the Golden State is losing its sheen. No one is comparing it to Greece these days, as some did after the last financial crisis, but plenty of business leaders and analysts privately point to the pervasive homelessness, volatile tax system and large unfunded pension obligations which are not being dealt with quickly enough. Worriers are right to wonder whether California and Texas are properly preparing themselves for the future.

9. Sources and links:

In addition to those quoted in the report, the author would like to thank:

Mark Baldassare, Oliver Bernstein, Sarah Bohn, Donna Campbell, Michael Cohen, Anthony Dalton, Erica Grieder, Lina Hidalgo, Matt Hirsch, Jacob Kaufman-Waldron, Ronald Kirk, Cappy McGarr, Janie McGarr, Jesse Melgar, Kathy Miller, Ardon Moore, Walter Robb, Jason Sabo, Katie Smith, Joe Straus, Sylvester Turner

Those who would like to read more about California and Texas may be interested in the sources below:

Centre for Houston’s Future, “Immigration: A Report on the Regional Effect of Immigration”

Delightful audio versions are available in the Economist App.

Another view: America’s First Third-World State:

If someone predicted half a century ago that a Los Angeles police station or indeed L.A. City Hall would be in danger of periodic, flea-borne infectious typhus outbreaks, he would have been considered unhinged. After all, the city that gave us the modern freeway system is not supposed to resemble Justinian’s sixth-century Constantinople. Yet typhus, along with outbreaks of infectious hepatitis A, are in the news on California streets. The sidewalks of the state’s major cities are homes to piles of used needles, feces, and refuse. Hygienists warn that permissive municipal governments are setting the stage — through spiking populations of history’s banes of fleas, lice, and rats — for possible dark-age outbreaks of plague or worse.

High tech does its part not to clean the streets but to create defecation apps that electronically warn tourists and hoi polloi how to avoid walking blindly into piles of sidewalk excrement. In Californian logic, public defecation butts up against progressive tolerance, so it is exempt from the law. Yet for a suburbanite to build a patio without a permit, for example, costs one dearly in fines. Indeed, a new patio without a permit can be deemed more dangerous to the public health than piles of excrement in the public workplace.

One out of three Californians who enters a hospital for any cause is now found to be suffering from either diabetes or pre-diabetes, an epidemic that hits the Hispanic community especially hard but for a variety of reasons has not led to effective public-health efforts and sufficient publicity. State-run dialysis clinics now dot the towns and communities of the Central Valley — a tragic symptom of dietary culture, massive illegal immigration, and poor public-health education.

I’ve been blessed to live in and visit Texas and California. Both feature beautiful geography, interesting people and boundless opportunity.

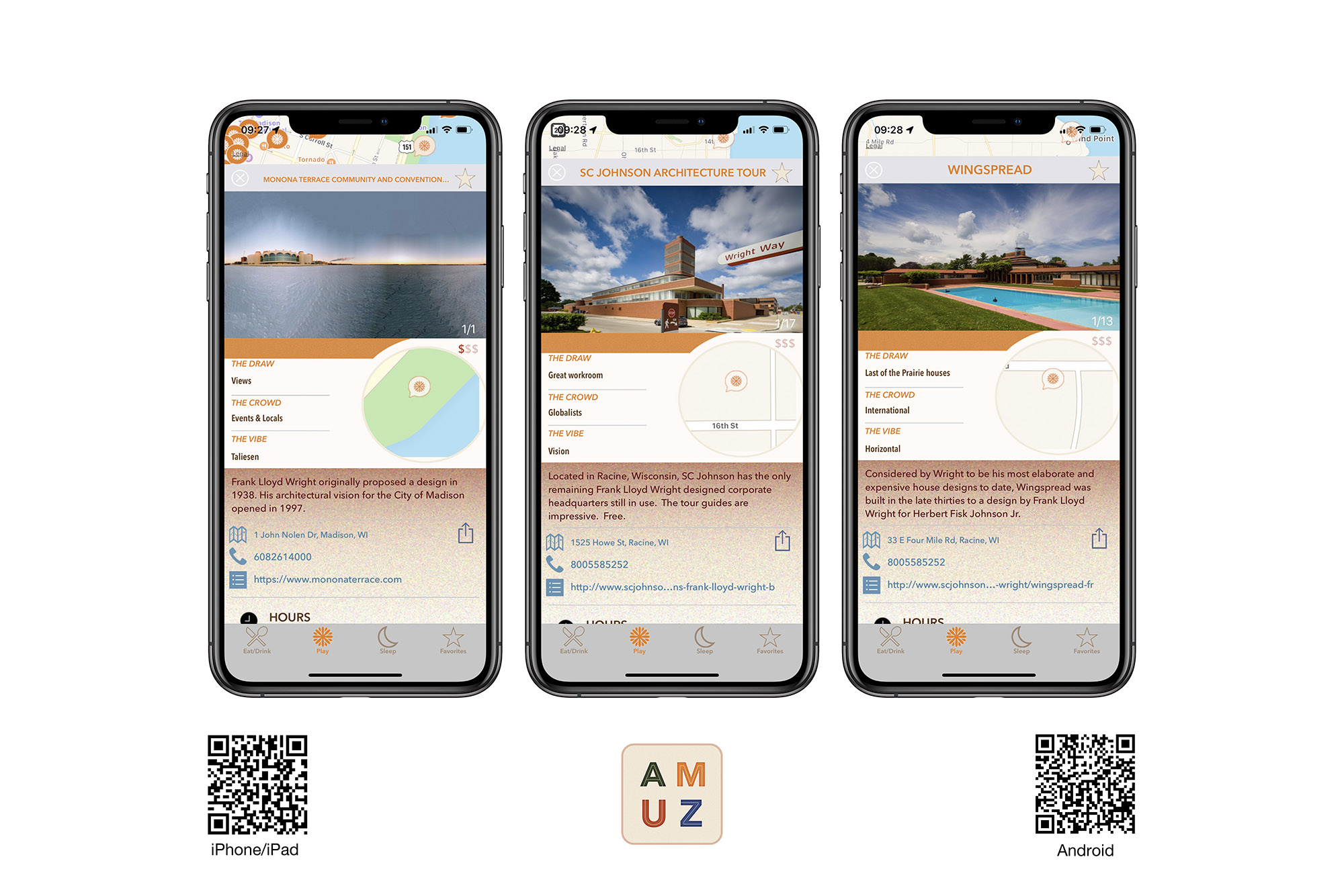

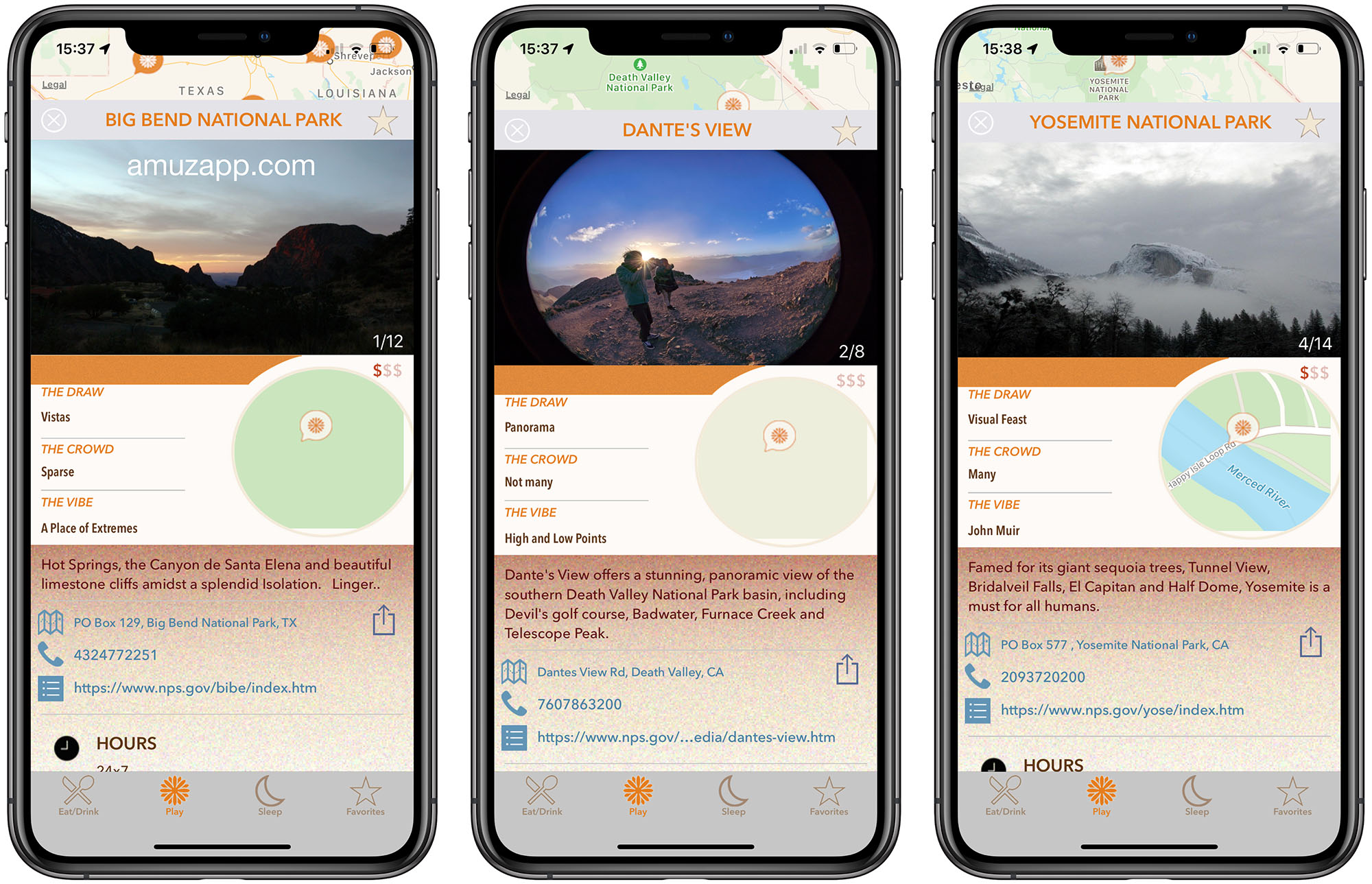

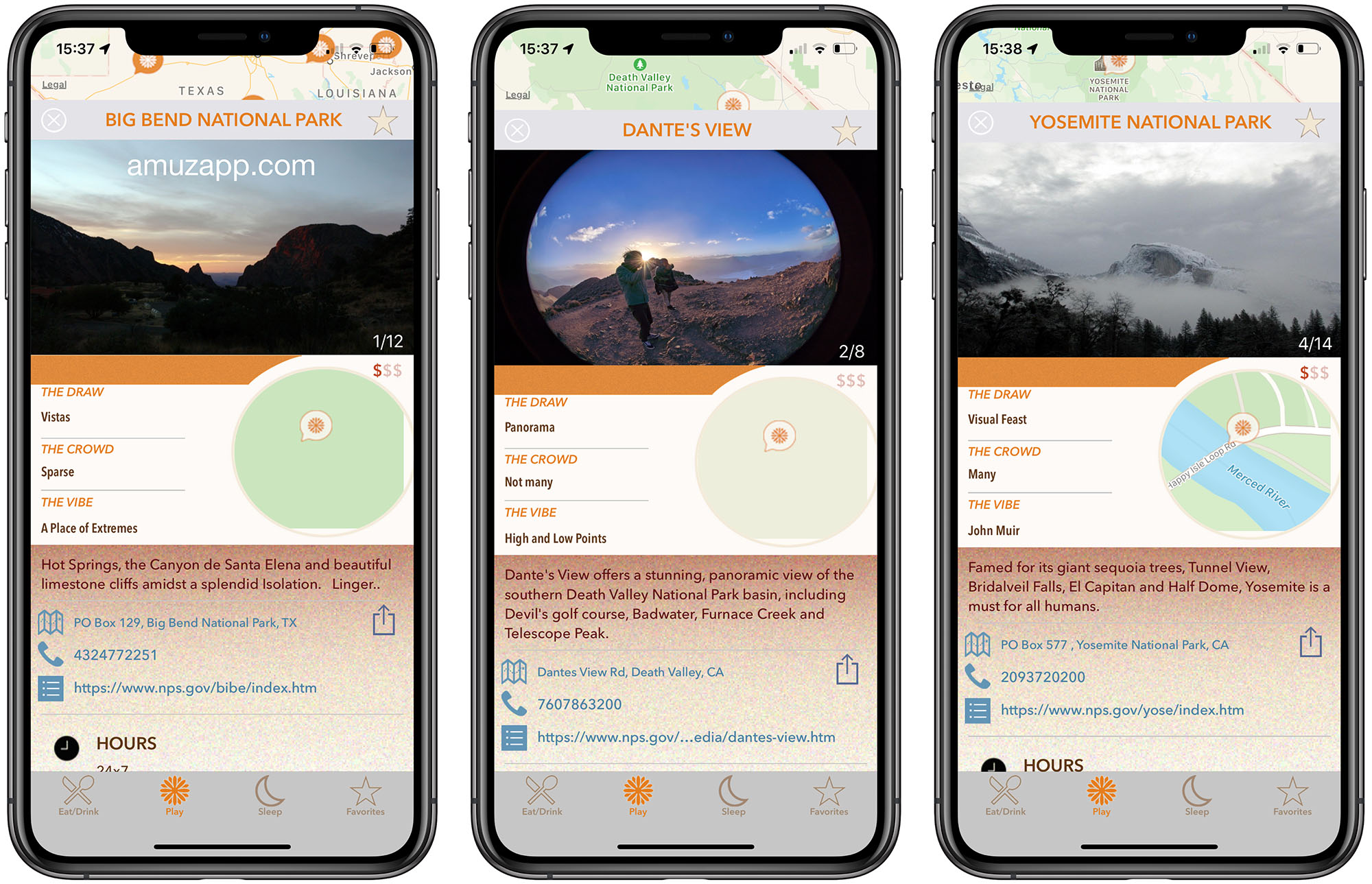

Explore Big Bend, Yosemite and Death Valley National Park along with many other interesting locations in the amuz app.